What the Advertisers Sold

In addition to subscribers, advertisements in newspapers serve more than as a financial source to sustain these papers. They offer a picture of the society that publishers, editors, and readers shape together in the medium of commercial goods and services. In particular, Black newspapers suggest the ways in which African Americans participated in the American economy at the time when political denial of Black citizenship hampered their economic advancement as well. A series of laws known as the “Black Laws” was enacted in Ohio, beginning in 1803, to discourage free Black people from settling in the state and thriving economically. One of the laws required any new African American settler to post bond for $500 (equivalent in purchasing power to about $12,238.45 today) and file evidence of free status.[1] They were not permitted to work unless they carried a document to prove their payment of the bond and free status. Even if they paid the bond, they were consecutively obligated to pay taxes often without having civil rights like voting and public education.

The list of advertisements for Black-owned businesses exemplifies Black Ohioans’ triumph over and disruption of the racist policies that exclusively praised white economic success with the “self-made man” trope. Of course, we should not conclude that all the businesses advertised in the Black newspapers were owned solely by Black Ohioans. Nevertheless, the majority of advertisers in them were about Black-operated stores and services that specifically targeted Black customers who would subscribe to these papers. As the overview of the advertisements published in the Ohio Black newspapers in the 19th century suggests, African Americans in the state gradually came to have various types of business. This diversifying trend of Black consumers/readers’ interests were congruent with the increasing Black population and opportunities for politics, education, and economy throughout the century.

Multiple Businesses Owned by a Few Front Runners in the 1840s

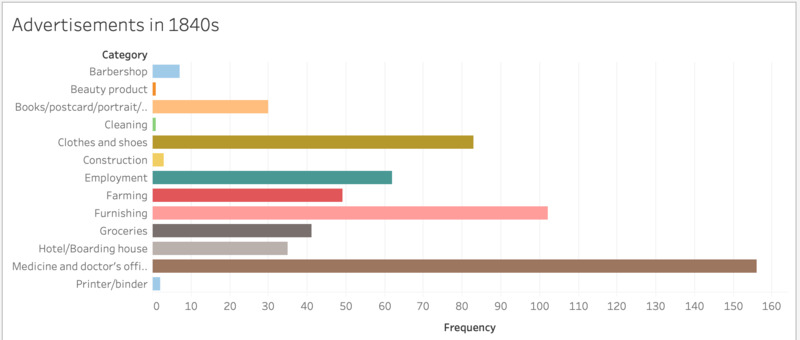

Advertisements in the Palladium of Liberty show what kinds of business early African Americans in Columbus operated, and what goods and services they would look for. In contrast to some studies arguing that most early Black settlers lived in rural areas of Ohio, the newspaper allows us to witness a thriving Black community in an urban area like Columbus and its satellite communities in nearby rural ones.[2] As the graph suggests, three major categories of the advertisements in the Palladium of Liberty are medicine and doctor’s office, furnishing, and clothes and shoes, followed by other categories including employment and farming. Interestingly, despite these various categories of the advertisements, advertisers are mostly limited to a small number of Black business owners: G.W. Stanton, James Beckwith, J.B. Wheaton, and David Jenkins, the editor. This indicates that they, the leaders who helped new residents and young Black people to learn commerce, ran multiple businesses not only to achieve personal financial gain but also to vitalize a Black community at large.

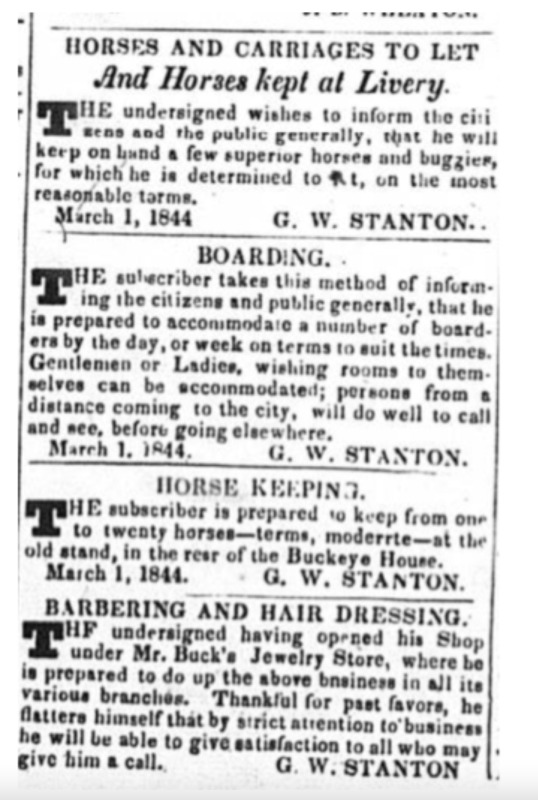

The four frequent advertisers were active members of the Columbus Black community and contributors to the newspaper. For example, G.W. Stanton appears as a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Columbus in “An Act to Incorporate Sundry Churches named Therein” in 1845.[3] He joined the seven Executive Committee from the second or third issue of the Palladium of Liberty. According to the advertisements on March 20, 1844, he possessed a large farm to host horses and buggies near the Buckeye House, a boarding house for both men and women, and a shop for barbering and hairdressing. This variety in businesses also leads us to assume that he had familial support and a large number of employees.

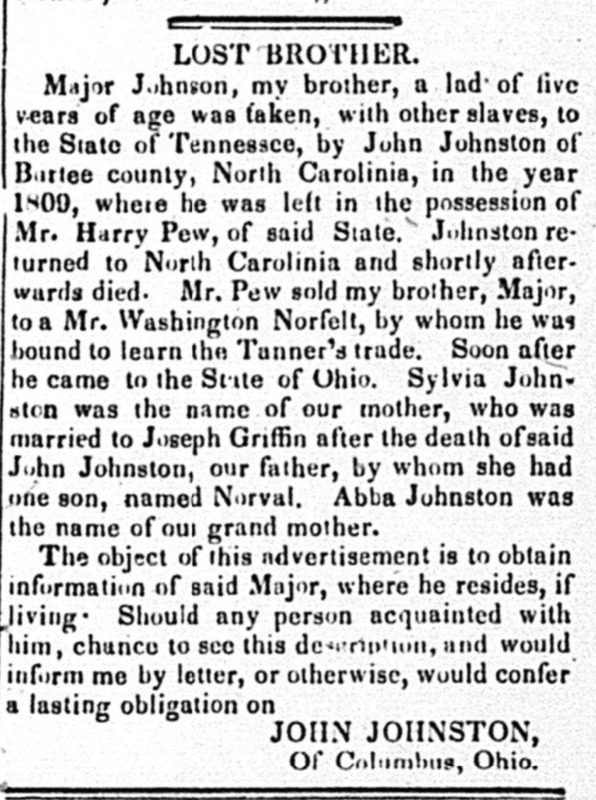

Some advertisements look for lost family members into slavery. Many of the first generation of Black Ohioans were formerly enslaved and self-liberated people from the South, maybe hoping that their kin could also have made their way into the free state.

More Business with Advanced Technology in the 1860s

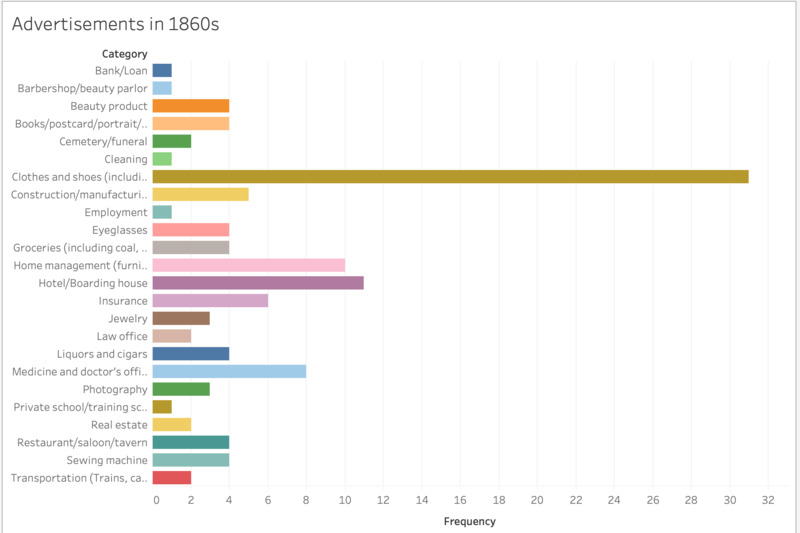

The absence of advertisements in the Aliened American a decade earlier keeps us from understanding Black business in the 1850s, especially in northeast Ohio including Cleveland and Oberlin, the two cities that served as political, educational, and economic hubs of emerging Black communities. Nevertheless, the diversity of Black businesses in the Colored Citizen of the mid 1860s hints at the continuous influx of African American settlers and their growing financial influence in Ohio. The political and economic dynamics caused by the Civil War also encouraged Black people to seek places where they would face less racist violence and more opportunity for their younger generation. Cincinnati, where the Colored Citizen was published, absorbed these newcomers from the South, attracting them with its established Black communities that had achieved public education for Black children years ago through political organizing.[4]

The advertisements in the Colored Citizens show two new trends of Black Ohioans’ lifestyle. First, the advancement of technology was distinctive. While clothes and shoes were most frequently advertised, advertisements for sewing machines and photographs appeared for the first time. This mechanization of clothing production accelerated the clothing market, resulting in many Black-owned businesses and their customers in the Queen city. Second, the advertisements in the paper reveal that Black residents needed legal service related to the Civil War. During the War, the newspaper served as a “Soldiers’ Organ” that informed military families of Black infantries in the battlefield and of benefits for veterans. Because of the racially discriminatory policies against Black soldiers in terms of military benefits, the Colored Citizen contains advertisements for legal assistants on their behalf like “Borden and Andrews,” one of the U.S. military benefits claim agents for Black veterans.

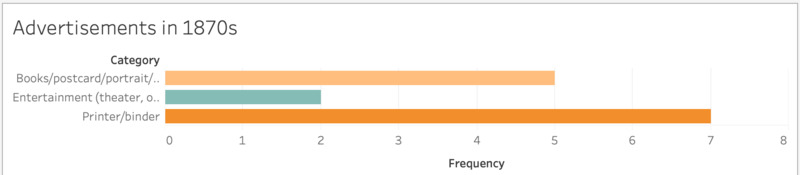

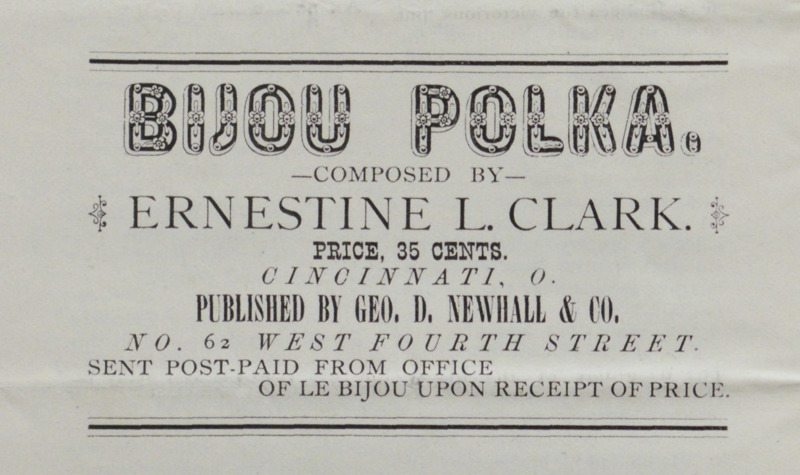

Between Culture and Market in the 1870s

Le Bijou does not carry advertisements as many as other newspapers for general readers because of its specifically targeted readership, adolescent readers. The newspaper still suggests that the editor, Herbert Clark, envisioned them to be culturally cultivated consumers in coming years. During the three years of its publication, Le Bijou included a limited number and categories of advertisements such as printing service, printed materials (books and posters), and entertainments. Instead of actually promoting commercial gains, these advertisements rather introduced young readers to ways of becoming highbrow consumers who would purchase cultural products like books and theatrical performance.

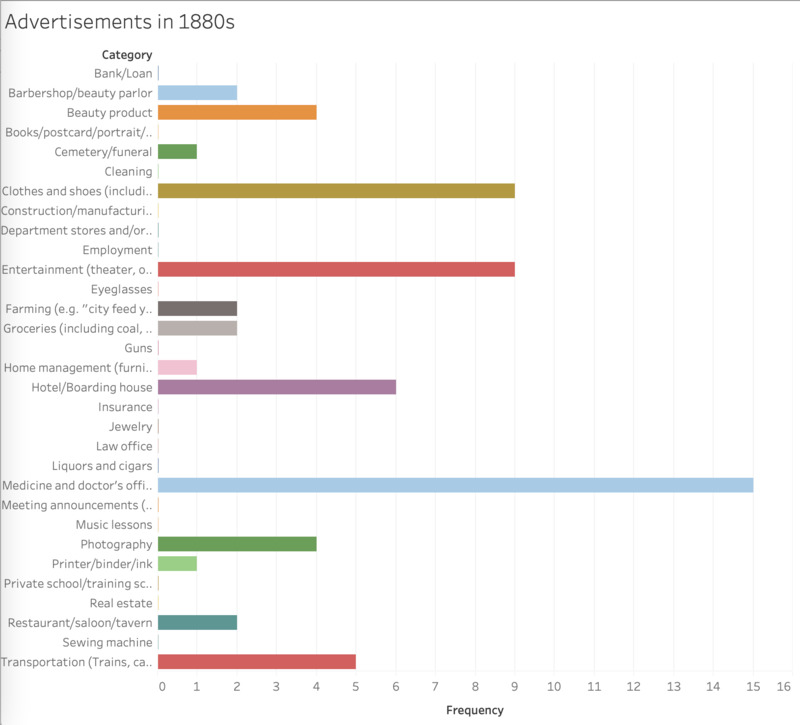

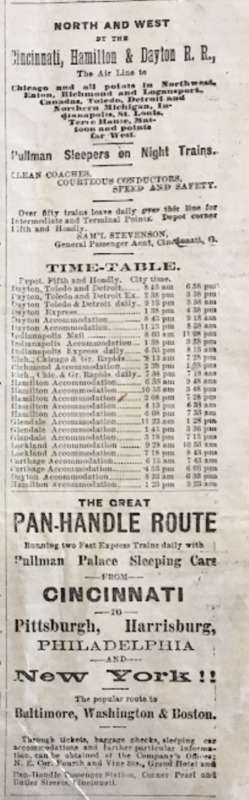

Advertising Mobility in the 1880s

Following the overall trend of advertisements throughout the 19th century, the number of categories of advertised products and services expansively increased in the 1880s. Although advertisements for clothes, boarding, and medicine constantly appeared as the staples of Black-owned businesses, African Americans emerged to be consumers of entertainment such as live performances at theater. If we extend the realm of entertainment to advertisements for leisure-related non-essential items including beauty products, music lessons, firearms, liquors and cigars, and restaurants, Black Ohioans in the 1880s seemed to have a culturally and economically more affordable lifestyle than the previous decades. In addition to the unprecedented opportunities for entertainment, the regular appearance of railroad time tables in the newspapers proves that Black Ohioans achieved mobility despite the atrocities of segregated trains in many states.

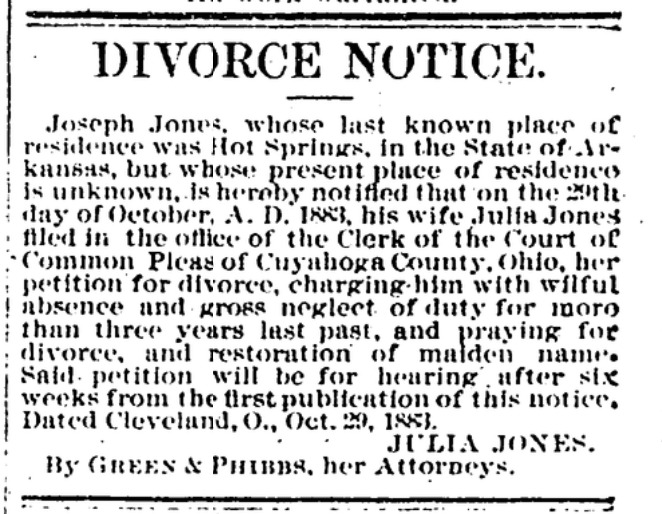

Divorce was still stigmatized as a mark of moral and religious failure, especially for women, who were imposed to maintain ideals of domestic life, although legally breaking marriage was not uncommon even in the 19th century. In the Cleveland Gazette, one woman publicly announced her divorce on the advertising page because her former husband was out of reach, wanting to have her maiden name back.

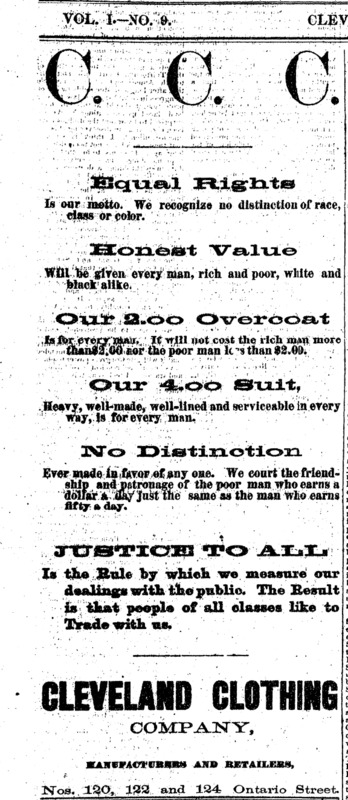

The Black newspapers in Ohio reveal that African Americans used their business as a platform for political change. While a financial success in the U.S. market economy was considered a sign of a person’s achievement through hard work in the 19th century when the “self-made man” ideology euphonized the harsh reality of competitive market, Black business owners were aware that their personal pursuit of profit should not be separate from a benefit for community. For example, the advertisement for the Cleveland Clothing Company, which was placed on the first page of the newspaper unlike other advertisements, declares that “Equal Rights is our motto. We recognize no distinction of race, class or color.”

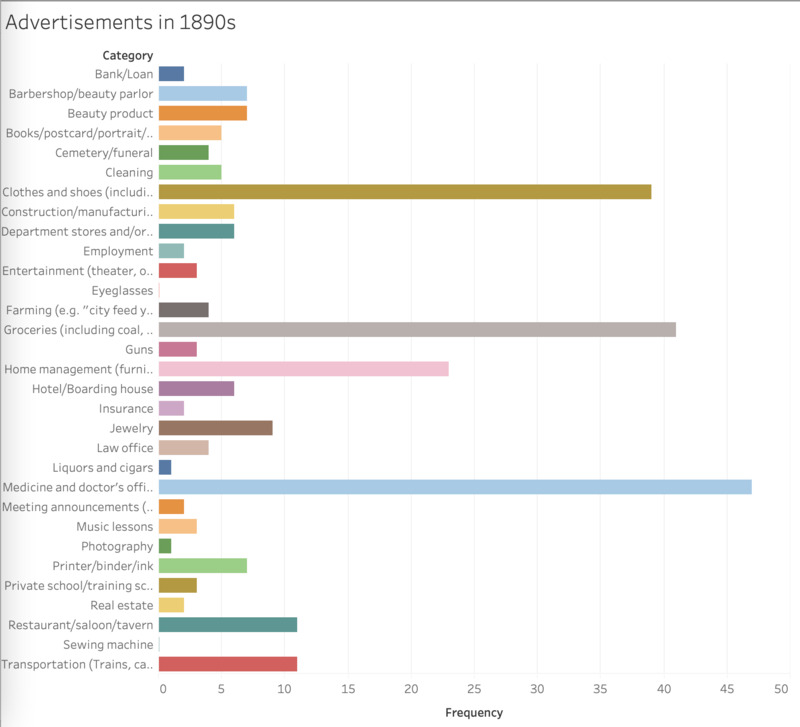

Visualizing Consumer Power in the 1890s

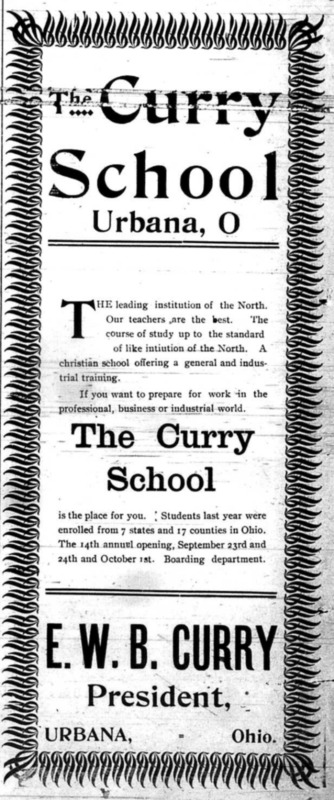

In the last decade of the 19th century, the Black newspapers in Ohio show that both categories and frequency of advertisements increased, indicating a large number of African Americans settled in urban and educational centers. Many publishers and editors of the newspapers were also business owners (P.W. Chavers of the Columbus Standard), educators (Elmer W.B. Curry of The Informer and D.H.V. Purnell of the Ohio Standard and Observer), and politicians (Harry C. Smith of the Cleveland Gazette) who employed the press as a vehicle for their messages on these career-related interests that would advance the life of African Americans. Advertising in their papers was not an exception for this practice. The editors viewed that subscribers were not limited to those who could purchase advertised items and services, but they were also prospective students, citizens with political power, and future business partners.

Advertising technology also advanced; for example, illustrations and photographic images were often included in advertisements to attract potential consumers, like an advertisement for the Globe Steel Ranges.

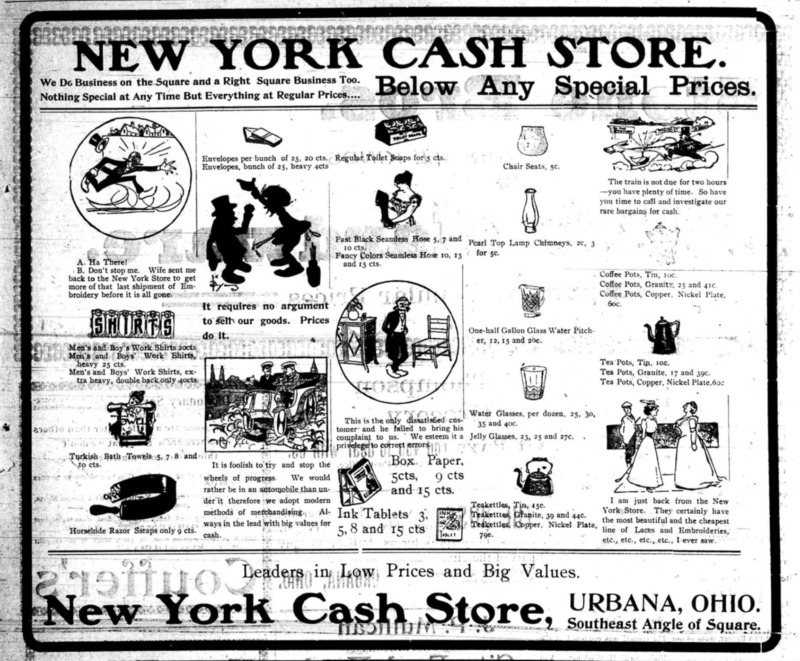

In addition to visual images in advertising, the newspapers contain advertisements adorned with eye-catching humor and phrases, as one for the New York Cash Store, published in The Informer, exemplifies.

[1] “$500 in 1803,” CPI Inflation Calculator. Accessed November 25, 2021.

[2] For example, David Meyers and Elise Meyers Walker’s Historic Black Settlements of Ohio (The History Press, 2020) trace legal documents such as a former enslaver’s purchase of land where his once enslaved people would be located, focusing on land ownership as the evidence of early Black communities.

[3] N. Willis, Printer to the State, Acts of the State of Ohio, Vol. 43.

[4] Black Cincinnatians founded the Cincinnati Independent Colored School System in 1856, which continued to operate for the next eighteen years. African American voters elected a school board consisting of only Black candidates. Some of the elected officials like Peter Clark worked for Black newspapers.