What the Subscribers Read

Topics in the newspapers hosted in this project show various aspects of early Black communities in Ohio. First, we can see what contemporary readers looked for in the newspaper. Their interests reveal the relationship that individual readers had with their community at familial, local, national, and even international levels. Second, newspaper topics tell what editors and publishers aimed at through its publication. Like most Black periodicals in the 19th century, publishing newspapers in Ohio was an unprofitable business, for which editors and publishers often had to maintain jobs other than working for the paper until Harry Smith as a full-time newspaperman started the Cleveland Gazette in 1883. Their occupations included barbers, preachers, educators, civil servants, librarians, business owners, but, of course, not limited to these. The diversity of the editors also implies that they helped the newspaper address manifold interests of various groups within the Black community. Third, topics in the newspaper lead us to hidden and anonymous contributors, most of whom were women and children, because their presence in public, even with only names in print, was considered inappropriate in the contemporaneous culture of the cult of womanhood. At last, the topic data reflects how Black Ohioans responded to historical moments in the 19th-century U.S. in order to achieve civil rights and demonstrate their civic qualification as model citizens.

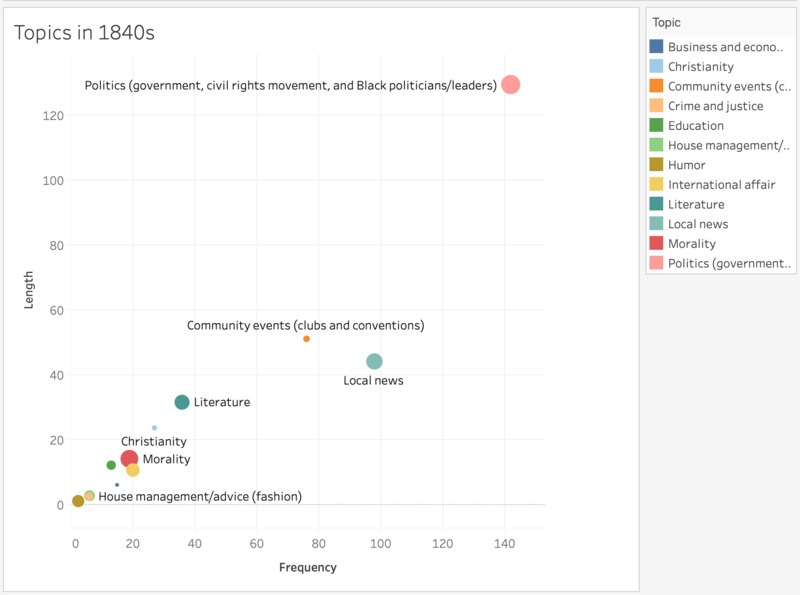

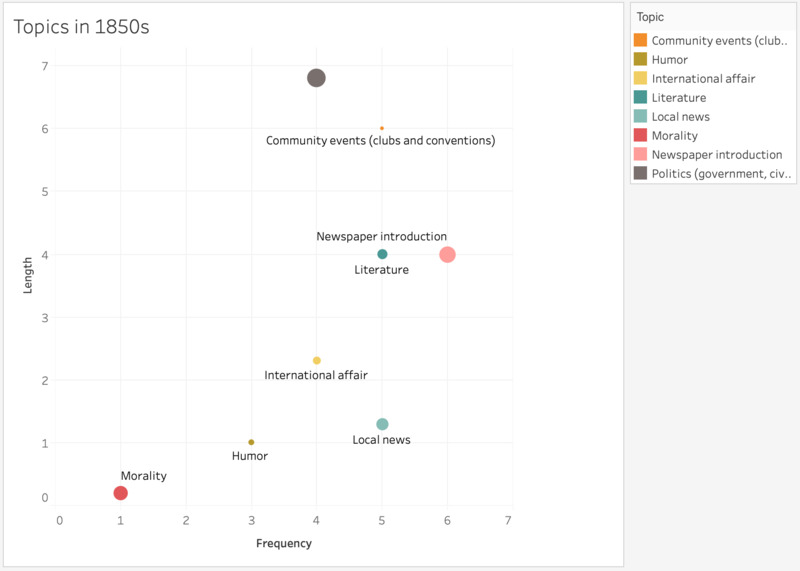

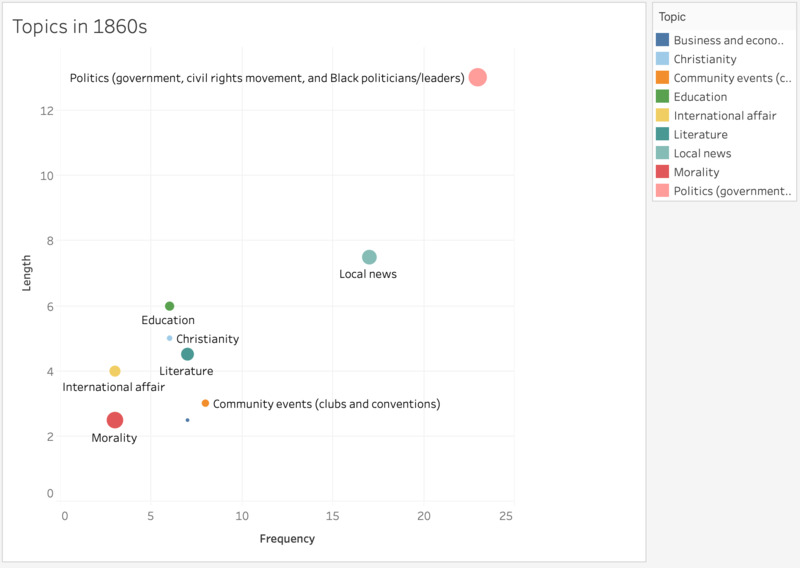

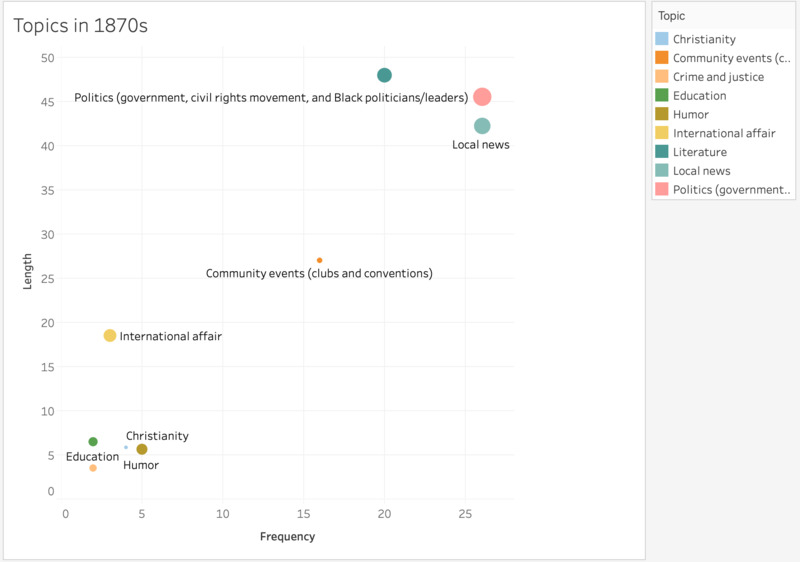

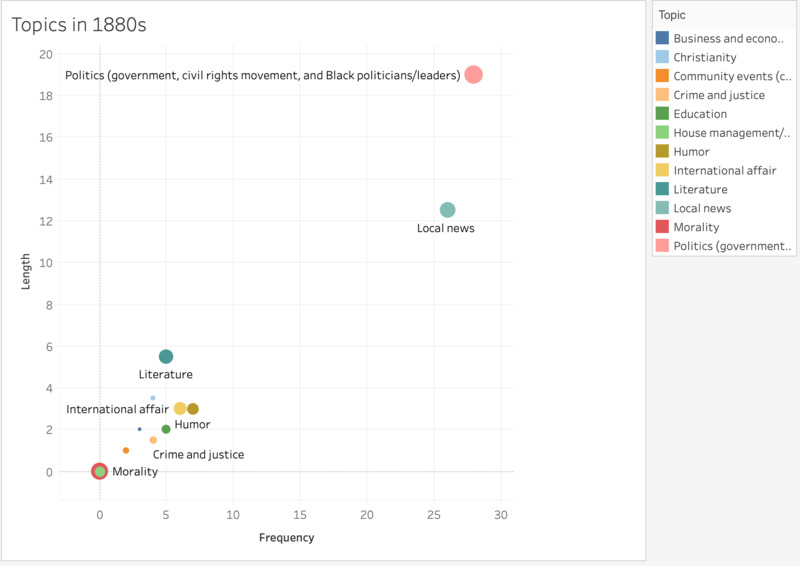

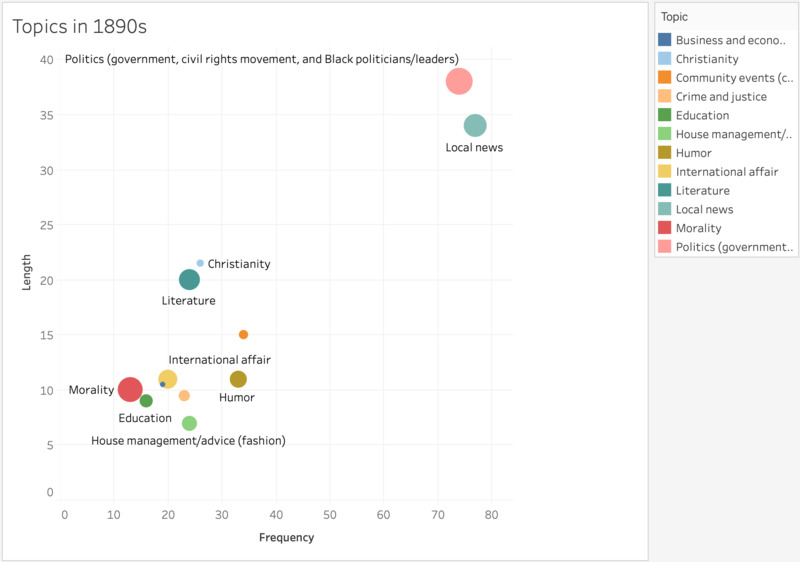

Data of the newspaper topics were collected from the sixteen available newspapers. The categories for the data include literature (short stories, poetry, and drama), morality, Christianity (sermon and church activities), education, politics (elections, colonialism, civil rights movement, and abolitionism), international affairs, humor, crime and justice, community event (conventions of Black citizens), business and economy, and home management. The data measures both frequency and length of a topic because they are not necessarily congruent with each other. For example, local news and community event notices frequently appeared but took relatively small space on the page of the Dayton Tattler. By contrast, political articles in the Aliened American not only frequently appeared but also were detailed in several columns. Both an article with a title and untitled short articles comprising one or two sentences were considered for the topic data. An article’s length was counted based on a rough total of how many columns it takes up.

Overview of the Topics throughout the Black Newspapers in 19th Century Ohio

This data site shows contents of the newspapers throughout the history of early Ohio Black newspapers in the 19th century.

In the Beginning of Ohio Black Press

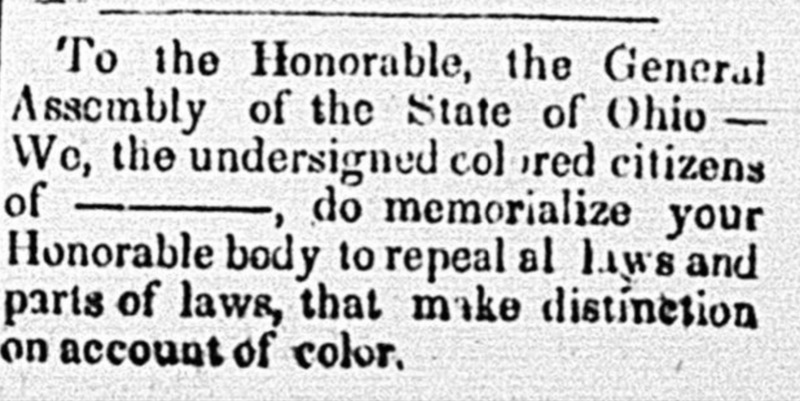

The Palladium of Liberty informed Black communities in Ohio of in-state and out-of-state news as well as international subjects, maintaining its strong political voice on behalf of people of African descent. The paper focused on contemporary politics beyond abolitionism and slavery. One of the most frequently mentioned topics throughout its one-year run is the annexation of Texas. The Palladium of Liberty criticized the government’s colonization of northern Mexico. In addition, although education of Black children and voting rights were priority for early Black communities in Ohio to ascertain their civil rights, the state law prevented them from exercising the rights while imposing taxes on their business and labor. Therefore, the newspaper suggested that the Black Ohioans as citizens actively participate in policy-making by submitting petitions to establish Black schools and to obtain voting rights.

To fight this systemic injustice against Black Ohioans, the Palladium of Liberty functioned as a site to educate people and to channel the readers into political actions for their communities. For example, the paper facilitated and reported on meetings and lectures by prominent Black leaders like Martin Delany. Self-liberated people like Henry Bibb were also invited to give testimony to their experience under slavery and liberation, following David Jenkins’s introduction to him.[1]

The Palladium of Liberty was not an exception from the debate on African colonization and emigration of African descendants, which polarized Black communities in free states in the mid-19th century. Many letters to the editors published in the Palladium of Liberty suggest that Black Ohioans in general objected to the idea of African colonization and emigration. One article says: “But must we go to African and leave all those that we have mentioned; as they may become content with these conclusions, no never, no never, who under heavens has placed us in our condition, who has torn us from our original homes, and now with a live branch of slavery, as this is the best name we can give it, reaching across the Atlantic ocean, biding us welcome to a land that flows with milk and honey[?]”[2]

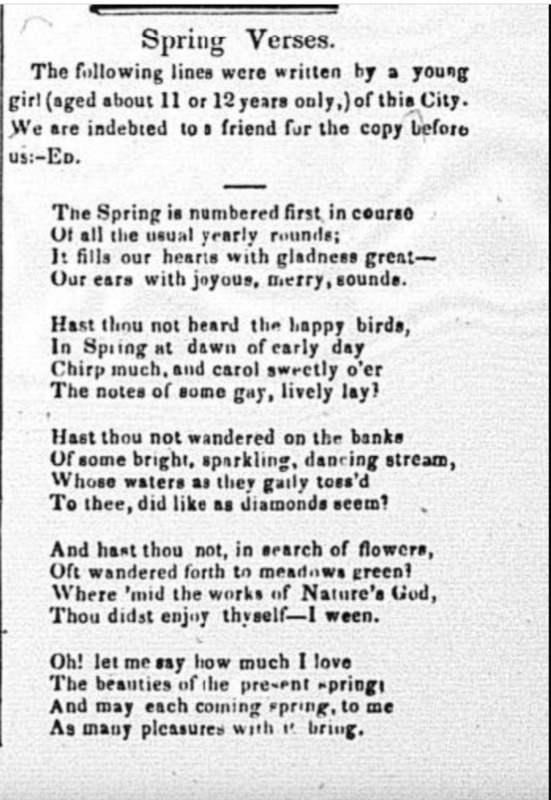

Along with politics, the newspaper significantly placed an emphasis on literary pieces. The first pages of most issues include poems or short stories. While poems carried themes of Christian faith, virtue, and freedom, short stories address the possible interest of young and women readers because they portray a young couple’s love story and courtship, romance of a young black woman and marriage, and a young man’s fantasy about a woman’s virtue. These fictions were published under unidentifiable writers because of their apparent pseudonyms like “W.H. Carpenter” and “Wm. Comstock.” One pseudonym is particularly noticeable: the newspaper once serialized “Liberty Hymns,” written by “A. Freedomite.” Eric Gardner notes that Black periodicals included literary pieces like the Recorder's "The Curse of the Caste" to recognize the diverse interests of readership, especially women.[3]

Given that the themes and tones of these literary pieces seemed targeted at women audiences, we may assume that the pseudonymous writers could be women writers who were associated with the editors of the Palladium of Liberty. For instance, David Jenkins’ wife, Lucy Ann does not appear in the newspaper but she possibly still contributed to the paper. She could have served as a recruiter of local women writers, as they often met under the domestic-concerned name of “sewing club” at her residency. As the following example--“Spring Verses,” written by an 11 or 12 year-old girl in Columbus--shows, the paper was open to young writers, who must have been encouraged by mothers and “aunties” to publish their works.

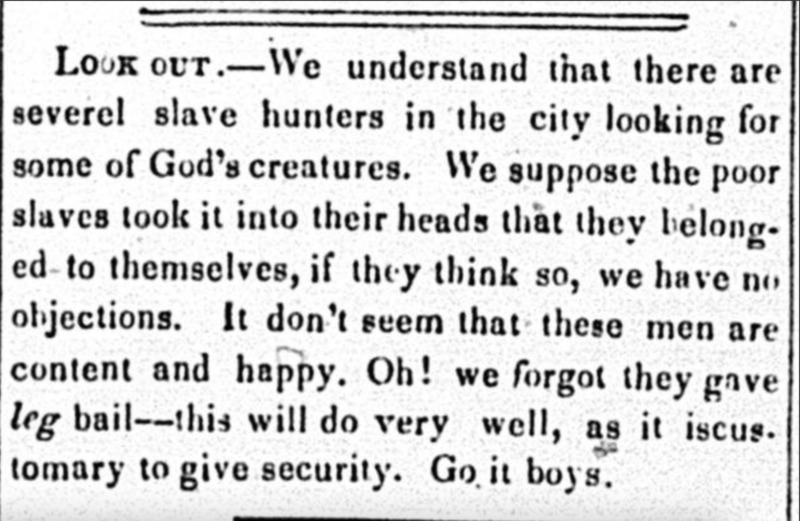

While the Palladium of Liberty published news in the local Black community such as marriage announcements and moves, it also reflected the specific hardships Black Ohioans in the antebellum period faced. Although Ohio was a free state, Black communities in the state constantly experienced racial hatred, discriminatory practices, and harassments. Even if lynching did not happen with the same frequency as that in the South, the “crime and justice” category tells that Black people were often attacked by whites, which were barely investigated by the authorities. As Ohio neighbored Kentucky and Virginia, both of which were slave states, the Palladium of Liberty suggests that Black communities in Ohio still experienced the danger of slavery not only because they actively participated in the Underground Railroad to help self-liberated people from slave states, but also because active agents of slavery freely came to Ohio to “hunt” for former slaves and their allies.

Celebrations of Black history and community building were not limited to conventions of free Black citizens. The Palladium of Liberty hints that Black Americans commemorated the Emancipation of the West Indies in 1843 by celebrating the day, the first day of August. By contrast to their enthusiasm for the independence of the West Indies, it is notable that the newspaper remained quiet about the Independence Day of the U.S., the Fourth of July. According to the newspaper, Black citizens in Ohio held the celebration of the Emancipation of the West Indies in at least three cities: Harveysburg, Columbus, and Newark in 1844.

Newspapers for Community Education in the 1850s and 1860s

Whereas the thirty-one issues of the Palladium of Liberty are available for us to mine a fairly consistent dataset in the 1840s, only three issues of the Black newspapers in the next two decades survived for our examination: one of the Aliened American and two of the Colored Citizen. Generalizing data from these three issues, as if they could represent how contemporary Black residents in Ohio lived, is problematic. Rather, the data from those newspapers are used to prove their specific roles in the Black community: the Aliened American as an intellectual elevation of Black people, and the Colored Citizen as an organ of Black soldiers and their families during and after the Civil War.

The inaugural issue of the Aliened American was claimed to be a sampler of the forthcoming paper for recruiting subscribers, even though we do not know how its following issues resembled this first issue. Like the newspaper’s motto, “To furnish news: To favor literature, science and art: To aid the development, education, mechanical and social, of colored Americans: To defend the right of humanity,” the Aliened American offers literary pieces, news on scientific advancement, and recent publications of well-known writers. And, targeting on Black readers in Ohio and the Lake Erie area, the newspaper reports various conventions organized by Black communities and political issues generated from the recent presidential election in 1853. It does not include any advertisement, although it contains a directory of potential advertisers that include both Black and white business owners in Northeast Ohio.

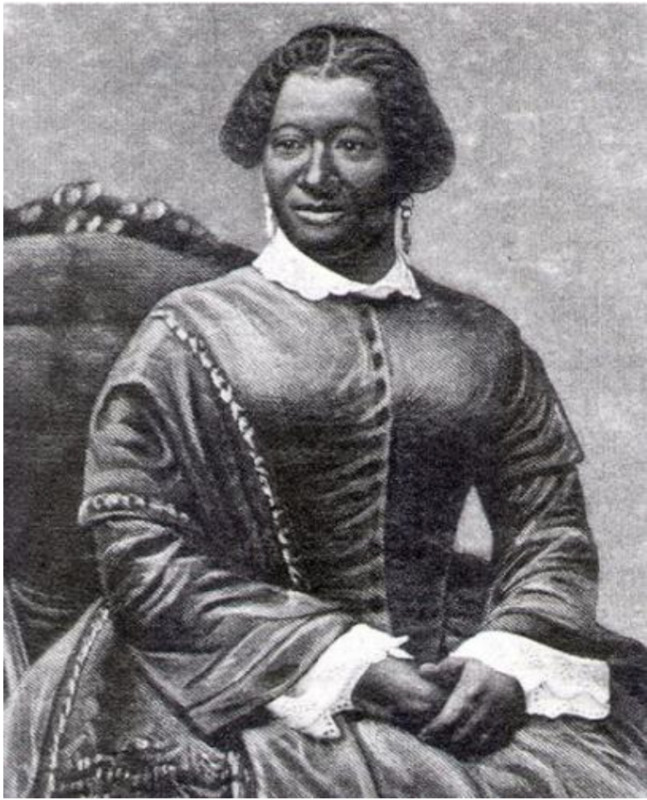

The Aliened American places literary works on its front page, aiming at readers who might be familiar with contemporary popular literature such as sentimental writing, religious poetry, and antislavery literature. The newspaper particularly spotlights Black-authored books such as Martin Delany’s The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852). Another book is William Cooper Nell’s Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1852). The most notable piece of literature in the Aliened American is a short story, “Charles and Clara Hayes,” written by William Howard Day’s wife, Lucie Stanton. With an embellished heading-- “Original Tale for the Aliened American”--the editor places the author’s name underneath the title. Given that many women writers had often published anonymously or with pseudonyms, printing her name must be a bold action to present her as a writer rather than Day’s invisible editor and domestic helper. You can find more about her in the following chapter, “Collaborative and Intimate Editorship: Lucie Stanton Day.”

Black artists as well as Black writers are highlighted in the Aliened American. Instead of glossing over news on their performance, the newspaper notes how they contributed to a Black community. This issue introduces the readers to Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, well-known with her appellation, “Black Swan,” not only for her popularity and successful performance at the Metropolitan Hall in March 1853, but also for her correspondence with New York City’s Black leaders to support the Home for Aged Colored Persons and the Colored Orphan Asylum. In addition to literature and arts, William Howard Day believed that scientific knowledge could enlighten the readers. The newspaper’s second page starts with a large heading of “Scientific,” in which the editor quoted a long article from the Hunt’s Merchant’s Magazine about the caloric ship that was powered by John Ericsson’s recent invention of a hot air engine.

As Ohio’s only Black newspaper in the 1850s, the Aliened American reports both regional and national conventions held by Black people. Like the editor says, “[Advertisements] are excluded by the proceedings of the State Convention,” the issue contains those of the Ohio State Convention of Colored Freeman in 1853, which was also published in a form of pamphlet and widely circulated in and out of the state. In addition to the state convention, the paper reports a county convention like Butler County meeting as well. It also includes the meeting minutes of the Ohio State Anti-Slavery Society, which was comprised of all Black leaders by that time, as well as the Anti-Slavery Convention at Cincinnati.

The most distinct political voice in the Aliened American can be heard in its criticism of the recently elected president, Franklin Pierce’s colonial expansionism. By placing the newspaper’s argument against President Pierce (page 3) prior to his inaugural speech (page 4), the editor leads its readers to witness his hypocrisy: while praising the democratic ideal of the U.S. Revolution, he promoted further colonization and annexation of other independent countries like Mexico and Cuba. The Aliened American speaks to and for Black Americans on the issue of African migration, in opposition to the settler colonial stance of the Colonization Society. While the newspaper does not promote Black people’s emigration to Africa, it also reports Black missionaries, like Sarah Margru Kinson Green, an African-native Oberlin-educated missionary and presumably acquaintance with Lucy Stanton.

Similar to the Aliened American, the Colored Citizen covers a wide range of topics such as international and national politics, science, literature, religion, and education. As its motto, “Nothing That Concerns Mankind if Foreign To Me,” the variety of topics in the paper evinces that it was intended to educate people of history, literature, and science in general while keeping them informed of Black soldiers. In its inaugural issue, the Colored Citizen announces that the paper is devoted to “the interest of the Ohio colored soldiers,” as one of the editors, Joseph E. Sampson responds to any inquiry about Black soldiers and veterans. One article praises them: “Our brave soldiers at Fort Hudson and Fort Wagner gave the rebels a striking evidence of their physical equality. . . Whilst our Dominican friends are convincing the slave holding Spaniards that they are not to be baffled and trifled with, our brave colored soldiery will respond to their welcome appeals of impartial law and liberty, with a vim that would have shaken the ancient battlements of Rome.”[3]

A humorous tone in reporting news is prevalent throughout the pages, implying that the newspaper might be intended not just for information but also for amusement at a gathering; that is, reading the paper together as a communal act, regardless of their literacy, education levels, and generational difference, would be a common practice of contemporary Black readers in the 1860s. For example, the Colored Citizen cites the Civil General, J.H. Buchanan’s article, “Obituary,” which announces the death of American slavery: “The monster has committed suicide, dying an ignoble death. No one seems willing to honor it so much as to prepare an obituary notice for the press.”[4]

The newspaper also offers a scientific approach against misinformation that people tend to believe. An article, titled “The Cholera,” warns the readers of unscientific rumors and fear of the contagious disease, and educates them how to prevent it based on recently proven evidence. The Colored Citizen uses statistics and data to report on the casualty of Black soldiers, which significantly exceeded that of white soldiers.[5] The paper includes a high volume of advertisements in comparison to the previous two newspapers, indicating that Black residents in Cincinnati actively engaged in business, education, and various services, in spite of the damages from the Civil War and the anti-Black riots in Cincinnati in the years of 1836 and 1841.

As Local News Outlets for Black Ohioans in 1870s and 1880s

The topic data of the 1870s newspapers is solely mined from the six volumes of Le Bijou from 1878 to 1880, while the extant copies of George Washington Williams’ Southwestern Review have not been located at the Western Reserve Historical Society, the only institution that has the physical paper preserved. The contents of Le Bijou deal with less taxing topics than other Black periodicals because it, as an amateur newspaper, was created by young-adult Black editors targeting equally young readership. Nevertheless, Le Bijou follows the tradition of the Black press with its emphasis on politics for Black civil rights, without compromising quality for the amusement of its young readership. The paper intends to cultivate adolescent readers with intellectual articles on history, literature, and interactive events. This Black-authored amateur newspaper envisions them to become active participants of American democracy as fully-recognized citizens.

One of the major contributors to the newspaper, Consuelo Clark (sister of Herbert Clark, the editor) not only introduced literary works by adolescent writers but also offered literary criticism that would help these writers produce high quality works by observing other contemporary young writers’ practices and readers’ responses to them. Le Bijou also connected its readers to other adolescent journalists and literary circles. The “local news” in the paper usually includes introductions to other amateur newspapers, while the “community events” encourage the readers to attend gatherings of young writers and journalists. These events often happened without a racial line, but the controversy over Herbert Clark’s election to be the Vice President of the National Amateur Press Association in 1879 exemplifies the racial tension within the community.

In the 1880s, there were more Black newspapers than before, even though we have only the limited numbers of their extant copies except Harry Smith’s Cleveland Gazette. The total four newspapers--Free American, Cleveland Gazette, Colored Patriot, and Afro-American--demonstrate a change of Black readership. Whereas their interest in politics still remains outstanding, these newspapers faithfully serve their local communities. Differently from the earlier newspapers like the Aliened American that straddles the line between a national political agenda and a local demand for a regional news outlet, these papers in the 1880s confirm their roles as a community news channel that prioritizes local politics and news. Likewise, the popularity and longevity of the Cleveland Gazette resulted from its dedication to Black communities in Cleveland that had grown up substantially because of the economic boom and influx of Black Southerners to settle in the Midwest in the 1880s.[6]

Even before the Supreme Court overturned the Civil Rights Act of 1875 on October 20, 1883, Black Ohioans were keenly aware of the tenuousness of their political rights that had been impeded by the State from the beginning of its establishment under the U.S. in 1803. Nevertheless, the 1883 case virtually stripped the federal government of any power to ensure African Americans equal protection under the law. As a result of the ruling, racially discriminatory practices in public places became immune to legal punishment. This means that public space--including newspapers--appeared to be one of the most contested sites where Black Ohioans could prove and practice their civic quality. Harry Smith launched the publication of the Cleveland Gazette when the Civil Rights Act was challenged by several states, as its inaugural issue reports on Judge Mills’ decision in a civil rights case. Although all the issues of the Cleveland Gazette are not offered here, the 14 issues on this page include the titles of articles about the Civil Rights case. In particular, the issue on October 27, right after the decision, deals with African Americans’ response to the injustice and action to challenge the decision.

Diverse Readers and Various Interests in the 1890s

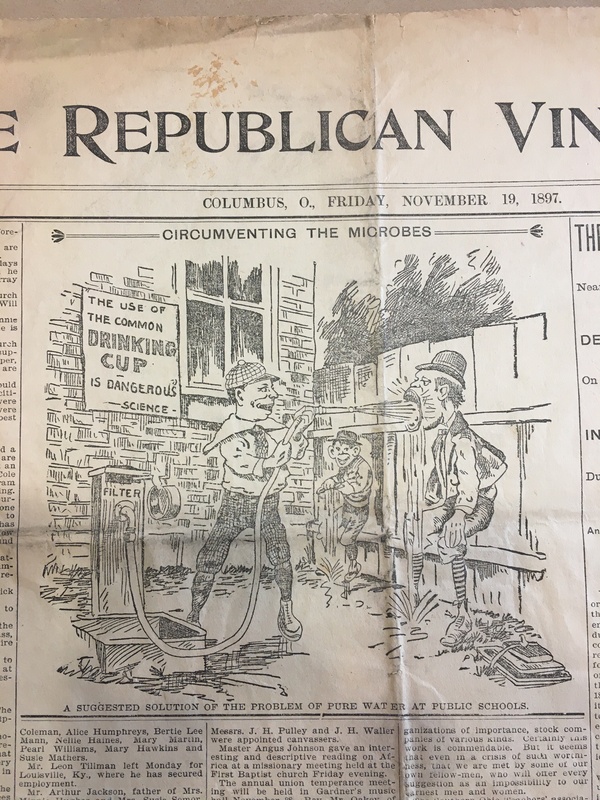

Whether or not they survived, Black periodicals continued to grow in the last decade of the 19th century. Harry Smith’s Cleveland Gazette successfully continued to issue every weekend into the 1890s, expanding its subscribers beyond Ohio. The seven newspapers, which are available for our examination, demonstrate that the number of subscribers increased, and that the newspapers diversified topics in responding to the growing readership. While politics steadily remained to be a priority, new topics such as morality and house management emerged significantly. The “morality” topic reflects that the subscribers became aware of moral issues regardless of their religious affiliations. Furthermore, both “business and economy” and “house management” are notable because they indicate that the subscribers could afford to invest in house improvement with increasing interest in financial management. This change also implies that Black residents in Ohio had a political influence, bolstered by the growth of their economic power, more than previous generations. From the 1890s, political cartoons began to appear in Black newspapers in addition to illustrations, which already became common, especially for advertisements, in the 1880s.

[1] “Mr. Bibb,” Palladium of Liberty, August 14, 1844, Page 2-3.

[2] “Colonization,” Palladium of Liberty, August 28, 1844, page 3.

[3] Eric Gardner, Black Print Unbound: The Christian Recorder, African American Literature, and Periodical Culture (Oxford University Press, 2015), 118, 228.

[4] “Honor to the Brave,” Colored Citizen, November 7, 1863, page 2.

[5] “Obituary,” Colored Citizen, November 7, 1863, page 4.

[6] Colored Citizen, May 19, 1866, page 1 and 2.

[7] Unfortunately, any data from the Cleveland Gazette has not been included in this visualization because of a licensing issue.