Editor and Agents

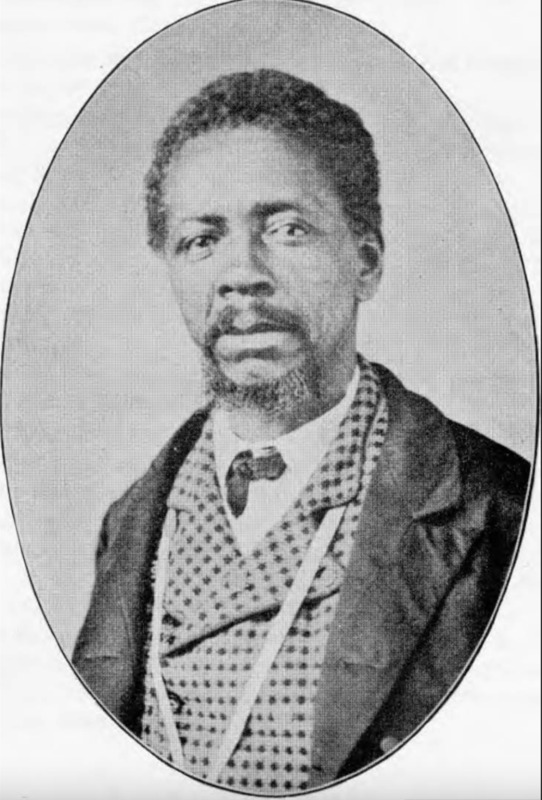

Editor: David Jenkins (1811 – September 5, 1877)

David Jenkins was born in Lynchburg, Campbell County, Virginia, in 1811.[1] His father, William Jenkins provided David with private tutors, noticing the young Jenkins’ potentials, until his knowledge was profound enough to teach his younger siblings. It is not clear whether his father was white. However, no other records of Black Jenkins have been discovered in Virginia. At least, Jenkins listed Virginia as his origin in the U.S. Census for 1850. He married Lucy Ann Mina James, a free person of color, on February 3, 1835, in his hometown.

Jenkins moved to Columbus in 1837 with his wife and gradually gained his fame as a community leader. Beginning with the National Convention of Colored Citizens in Buffalo in 1843, Jenkins as a delegate and committee members attended numerous state, national, and international conventions, including the North American Convention held in Toronto, Canada in 1851, until 1871 when his name appeared the last in the Proceedings of the Ohio State Convention of Colored Men. He was elected as a president at the state convention, in 1851 and in 1856, and became one of the central committee members in 1852.

David Jenkins collaborated for Black civil rights movements with other prominent African Americans in Columbus including James Poindexter, John Ward, and George Williams to organize the State Conventions of the Colored Citizens of Ohio. He also participated with the most Worshipful Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons for the State of Ohio, and recruited for the 127th USCT Infantry Regiment during the Civil War. Additionally, Jenkins served as an agent of the Underground Railroad. John Ward recalls Jenkins: "Coming from a slave state he had neither education nor money. He found the condition of the colored people here littler better than it was in Virginia, and though circumstances were against him, he commenced in earnest his labors, looking to the elevation of his people. "[2]

As the Palladium of Liberty often quoted Martin Delany’s The Mystery, a Pittsburgh-based Black newspaper published the same period as the Palladium, he was well acquainted with Jenkins’ versatile works for Black communities. Delany describes Jenkins:

David Jenkins of Columbus, Ohio, a good mechanic, painter, glazier, and paper-hanger by trade, also received by contract, the painting, glazing, and papering of some of the public buildings of the State, in autumn 1847. He is much respected in the capital city of his state, being extensively patronized, having on contract, the great “Neill House” [sic], and many of the largest gentlemen’s residences in the city and neighborhood, to keep in finish. Mr. Jenkins is a very useful man and member of society. [3]

Jenkins was listed as “painter” in the Columbus’s city directories of 1848 and 1862-1872 as well as in the Census in 1850, 1860 and 1870. But his work exceeded “painting" and was extended to large-scale construction. For example, the exclusive Neil House hotel, whose construction Jenkins and his workers built in Columbus, demonstrated architectural achievements in the 19th century, and served as a space for Ohioans’ public gatherings for a long time.

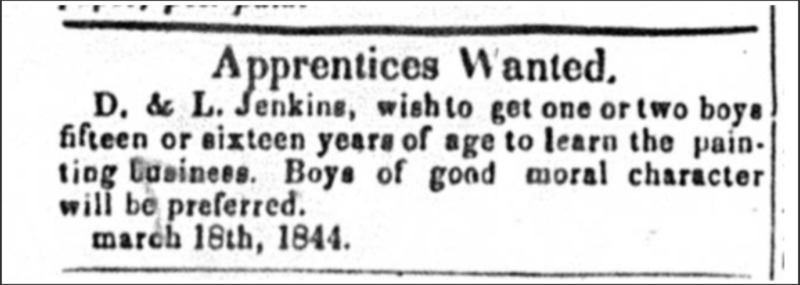

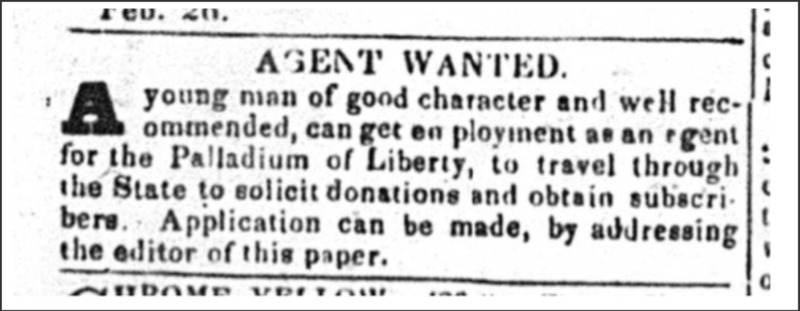

David Jenkins hired Black apprentices and employees because he believed apprenticeship was a form of education that the white dominant society hindered through the notorious Black law and other racist practices. Like the advertisement suggests, David Jenkins and his wife, Lucy Ann Jenkins, looked for young Black men who wanted to learn the painting business.[4]

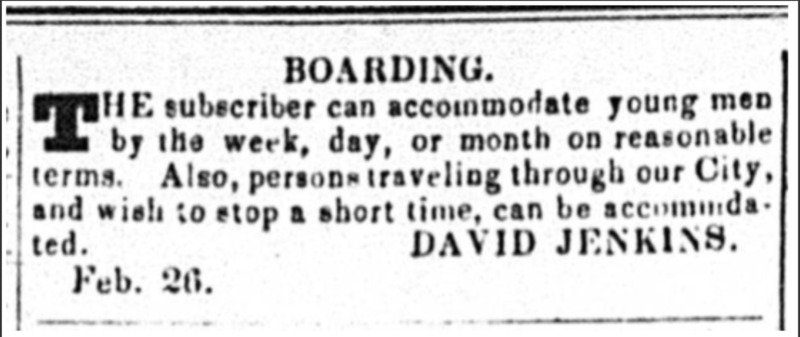

Jenkins’ dedication to Black education, especially his focus on practical skills in Ohio, started when he organized a “school society” with B. Roberts and C. Lewis and became trustees of the first school for African American children, presumably in 1837.[5] David Jenkins also ran a boarding house according to his advertisement. In considering his work for the Underground Railroad, we can guess that this boarding house could have served as a site for plotting the Railroad among agents. In the antebellum period, his residence and shop, which functioned as a boarding house, was located on Friends and High Streets in Columbus.

After the Civil War, Jenkins was disappointed that systemic oppression of African Americans had persisted. He lamented: “Except in Toledo, there are no (black) policemen, nor have there been any. No colored man has attained to the dignity of a deputy sheriff, deputy auditor, deputy recorder or deputy clerk."[6] He moved to Canton, Mississippi, after 1872 or 1873, as he accepted a position in Mississippi with the Freedmen’s Bureau and served as a Mississippi legislator in 1876.[7] After David Jenkins died on September 5, 1877, his widow, Lucy Ann, moved back to Columbus in 1879 and lived there till her death in 1899.

Agents of the Palladium of Liberty

Agents of the Palladium of Liberty recruited subscribers, collected fees, delivered printed copies, and sent news to designated regions, while most of them maintained their own businesses and jobs. Some of them also served as writers by sending letters to the executive committee for publication. During its one-year publication period, the newspaper hired 116 agents from five different states and even from England. Seventeen people out of the big group were traveling agents, most of them were clergymen. In particular, Rev. William C. Yancy, Rev. Thomas Woodson, and N. Nukes served from the beginning to the end of the paper. The first two also helped young editors publish a Cincinnati-based newspaper, Colore Citizen, in the 1860s. See this interactive map to trace the agents for the Palladium of Liberty

As the newspaper was created through the resolution of the National Convention of Colored Citizens and the Ohio State Convention in 1843, the Palladium of Liberty was introduced as a model of a Black newspaper that could address interests of African Americans. Many of the state and national convention delegates also served as agents for the newspaper. Nevertheless, it is not clear how far the Palladium of Liberty reached beyond Ohio; it had agents in Iowa and even Edinburgh in Britain in addition to the geographically close regions of Lexington, Kentucky and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Black residents in Pittsburgh could have better known about the Palladium of Liberty than any other big cities outside of Ohio because of the editor’s acquaintance with Martin R. Delany, who published The Mystery, the first Black newspaper in Pittsburgh.

[1] Dennis Charles Hollins’s PhD thesis, “A Black Voice of Antebellum Ohio: A Rhetorical Analysis of The Palladium of Liberty, 1843-1844” (Ohio State University, 1978) and Netti Ferguson’s essay in African-American Settlements and Communities in Columbus, Ohio: A Report (Columbus Landmarks Foundation, 2014) offer well-researched biography of David Jenkins.

[2] Ward, “David Jenkins and His Work,” Ohio State Journal, Feb. 25, 1870.

[3] Martin Robinson Delany, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (Black Classic Press, 1993), 99.

[4] “L. Jenkins” may represent “Lewis Jenkins” who was listed on the Executive Committee of the newspaper and active in the state conventions in Ohio.

[5] Netti Ferguson says that 1836 was the year he organized the society. But, as both Ferguson and Collins point out that Jenkins moved to Ohio in 1837, he must have organized it after his arrival to Ohio. African-American Settlements and Communities, 61.

[6] Cincinnati Commercial, August 23, 1873.

[7] DeeDee Baldwin, Against All Odds.