Herbert Clark and Le Bijou

Herbert A. Clark’s Le Bijou demonstrates one example of the boom of amateur journalism in the late nineteenth century. It says, "Published to please and satisfy the tastes of the girls and boys today." An amateur periodical was created to afford pleasure to its targeted young readers, not alone its editor and its publisher.[1] These young editors wrote, printed, and circulated thousands of issues, calling themselves “amateur journalists” and building their own network, “Amateurdom” or just “the Dom.”[2] But, most but not all amateur editors were juveniles, and not all articles in their periodicals were light-hearted literary pieces and reports. In particular, Black-led amateur periodicals offered educational and political articles for young readers who as citizens would be able to participate in leadership of the U.S.

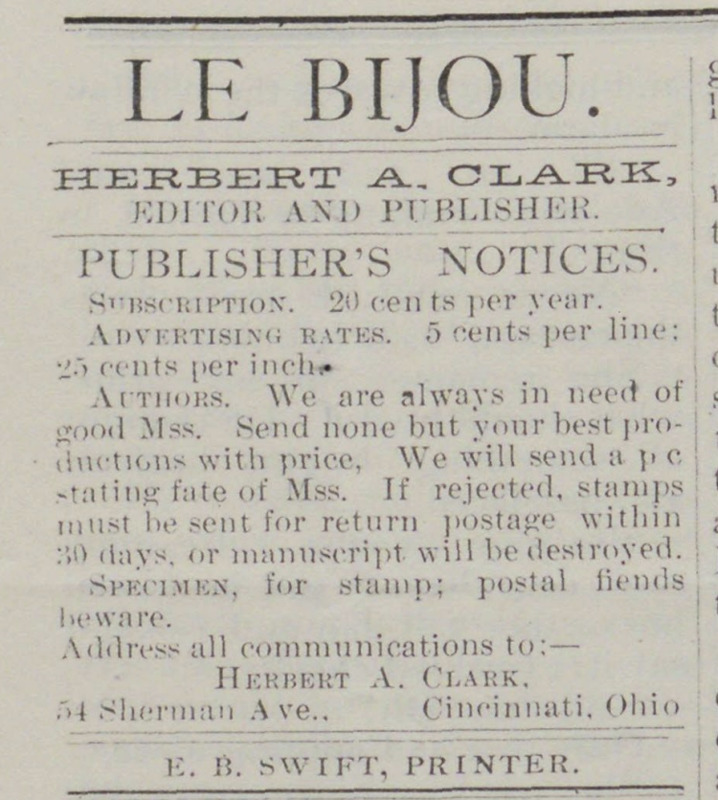

The first issue of Le Bijou came out in August 1878. The “Publisher’s Notices” indicates Herbert A. Clark as a sole editor and publisher of the newspaper. As the newspaper reprinted many different amateur periodicals, Clark seemed to have read and understood the amateur periodical market and readership well. He also requested that his readers send manuscripts for publication, encouraging young writers to publish. Despite the popularity of Benjamin Woods’ “Novelty Press,” it is not clear that Clark himself used the machine. Instead, Le Bijou was printed at the printing shop of E.B. White, who must have had the “Press” and ran his advertisement for his economic printing service throughout all the issues of Le Bijou.

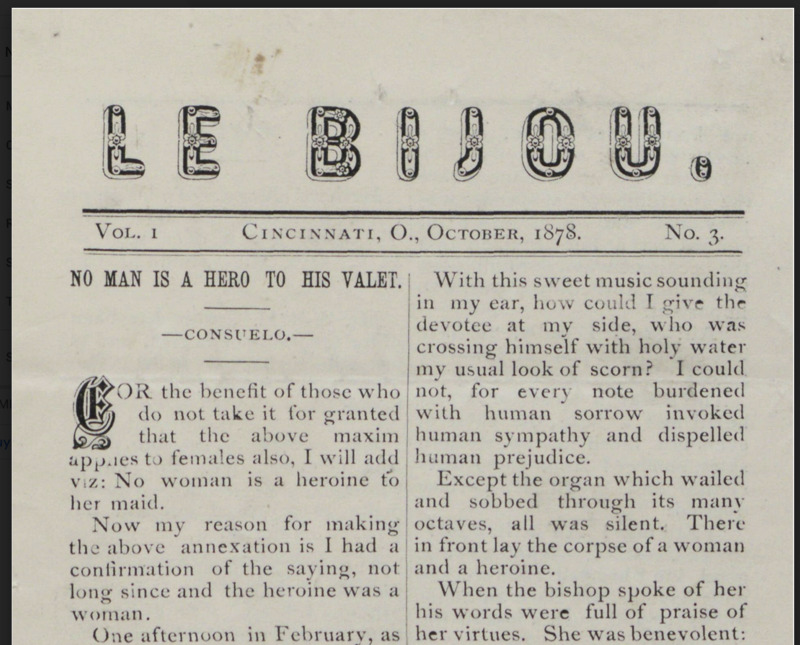

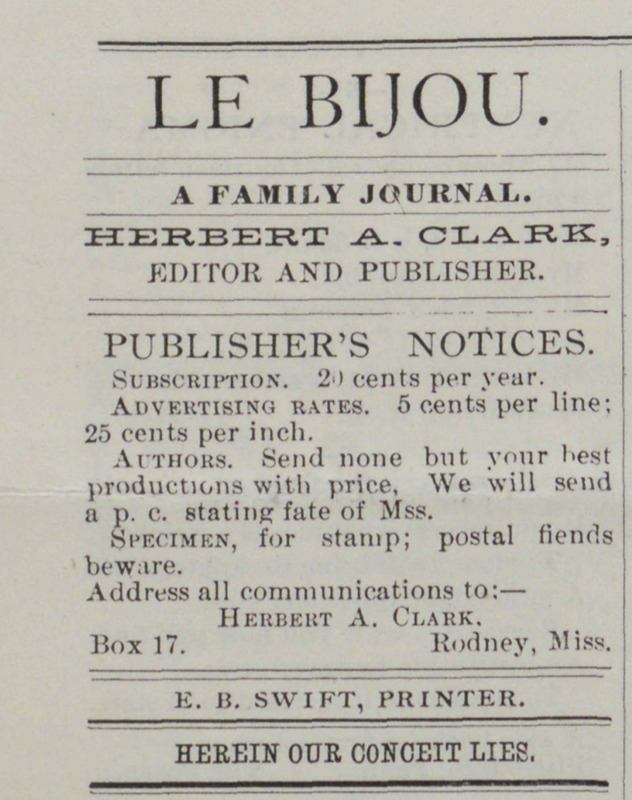

The publication of Le Bijou was a family effort, even though Herbert took the lead of the newspaper. From its third issue of the first volume, Herbert’s sister, Consuelo serialized short stories, journalistic articles, and columns. After Herbert moved to Rodney, Mississippi, so that he could teach Black children, Consuelo contributed to the newspaper more significantly. For example, she wrote more than half of the first issue (vol. 2, no. 1), which was published right after Herbert’s move to the South. In this issue, she also added the family’s address (54 Sherman Ave, Cincinnati, Ohio) to communicate with subscribers and contributors, instead of Herbert’s new residence in Mississippi. This indicates that Consuelo must have acted as an interim editor who oversaw the publication process from writing and accepting manuscripts to printing. [3] At this point, the newspaper began to self-fashion as a “Family Journal,” as if it aimed at family-centered education, cultural cultivation, and entertainment.

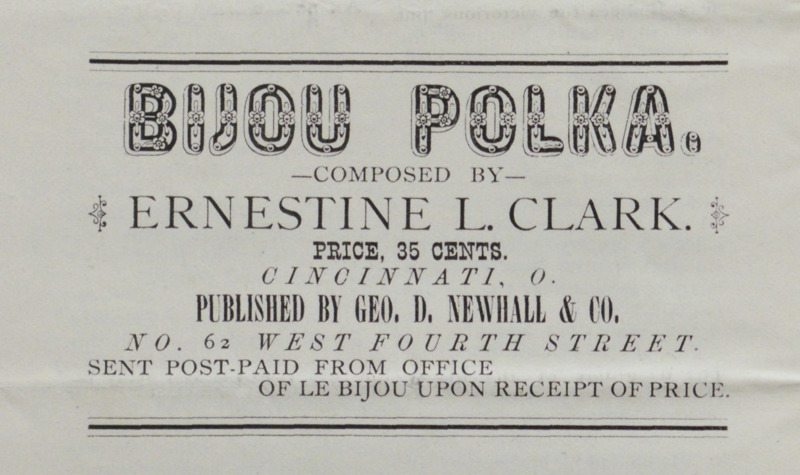

Another sister, Ernestine also contributed to the newspaper by offering articles on history and literature like “Early British History” (vol.2, no. 3, May 1879). Although her life is barely known, we can see that she sold her musical notes, titled “Bijou Polka,” from the advertisement published in many issues of Le Bijou.

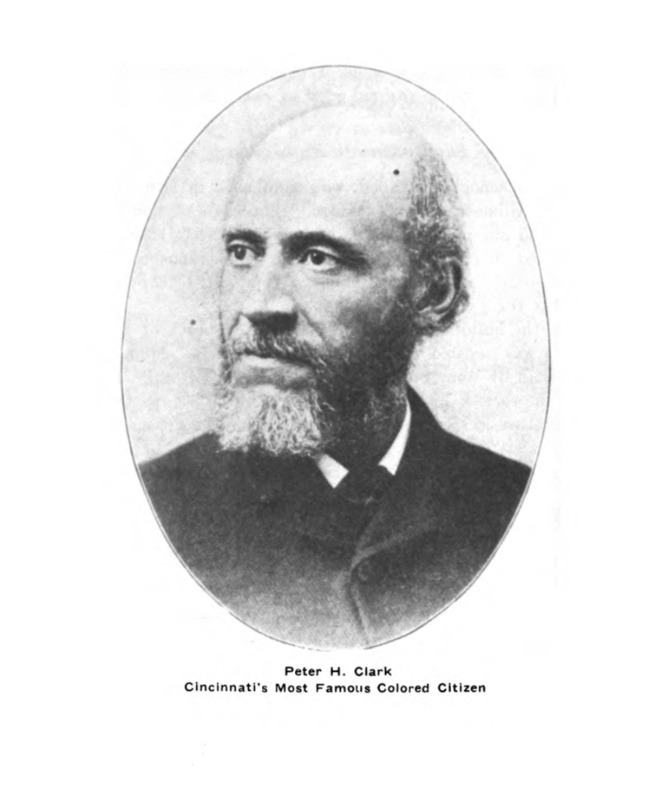

The newspaper as a product of the Clark family collaboration is not surprising. Their father, Pater Humphrey Clark was one of the earliest editors of Black newspaper in Ohio, as he published the Herald of Freedom in 1855--a Cincinnati-based in 1856. Even though his newspaper did not survive more than one year and no extant copies are available, his reputation as a journalist reached to Frederick Douglass who hired Clark for the Frederick Douglass Paper in 1856. Peter Clark came back to Cincinnati to serve as principal of the Western District School and ultimately to build a better education system for Black youths in 1857. Wendell Phillips Dabney estimates that “it is safe to say that from 1859 to 1895 not a teacher in the colored schools but had been trained by him [Peter Clark].”[4] He later moved to Alabama and then Missouri to continue renovating education for Black students. Hebert Clark followed in the footsteps of his father as an educator and newspaper editor. In 1882, the father and son teamed up to publish the Afro-American, with funds supplied by the Democratic Party.

Herbert Clark’s career as an amateur journalist is notable not only because he was the first Black journalist to be elected as the steering committee of the National Amateur Press Association (NAPA) in 1879, but also because his election recharacterized Leb Bijou in terms of politics and Black civil rights when most of the amateur newspapers dealt only with amusing topics for young readers. Clark claimed:

“Amateur journalism is commonly considered as an instructive pastime, fit for youths only. If we desire to prove it worthy of men, we must certainly lay aside all foolish ways and petty prattle. It must be our determination not only to interest men by the tone of our editorials, but to instill in them a generous respect, perhaps, a love for the case.”[5]

Even before the election of the NAPA, Clark seemed to have a notable reputation as an able editor because he could organize and host the NAPA annual meeting in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1879.[6] When Southern amateur newspapers criticized his election as the third Vice President of the NAPA solely based on his race, many of “the Dom” editors also supported Clark with the evidence of his leadership and professionalism, and the superiority of Le Bijou. This controversy was printed in the 1879 September issue of Le Bijou, while Herbert Clark himself maintained an objective and journalistic stance on the incident. However, Clark did not fail to report the blunt racism within “the Dom” community attentively and asserted Black citizenship and equality in the following issues. The Cincinnati Gazette introduced Herbert Clark:

“The last convention was held in Washington D.C. in July last, and at that time, Herbert A. Clarke [sic], of this city, was elected third Vice President of the association. The third Vice President is a son of Peter H. Clarke [sic], Esq., our well known colored citizen. Herbert himself is engaged in the work of training the youthful Southern mind at Rodney, Miss., and has been what is termed an amateur for several years, publishing in this city a neat little sheet, the ‘Bijou’.” [7]

Le Bijou ended in 1880 after publishing its sixth volume. Herbert Clark must have returned to Cincinnati sometime before 1882 so that he could collaborate with his father, Peter Clark, to issue the Cincinnati-based weekly Afro-American, the first Democratic African American newspaper in the U.S. And, he later bagan the first African American newspaper in Indian Territory.[8]

[1] “Amateur Newspapers,” American Antiquarian Society.

[2] Jessica Isaac, “Youthful Enterprises: Amateur Newspapers and the Pre-History of Adolescence, 1867-1883,” American Periodicals, vol. 22, no. 2 (2012): 158.

[3] Consuelo later became a doctor after graduating from the School of Medicine at Boston University. William J. Simmons and Henry McNeal Turner, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising (GM Revell & Company, 1887), 374-383. Documenting the American South. She remained active for Black communities in Ohio through her dedication to medicine. See Colored Convention Heartland: Black Organizers, Women and the Ohio Movement (September 10, 2021) Consuelo Clark. Retrieved from Colored Conventions Project.

[4] Dabney, Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens: Historical, Sociological and Biographical (1926), 107. Hathi Trust.

[5] See Le Bijou, vol. 2, no. 3. May 1879, page 6.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Qtd. in Le Bijou, vol. 4, no. 1, November 1879, page 4.

[8] See Paula Petrik, "The Youngest Fourth Estate: The Novelty Toy Printing Press and Adolescence, 1870-1886," in Small Worlds: Children and Adolescence, 1850-1950, ed. Elliott West and Paula Petrik (Lawrence, University of Kansas Press, 1992), 125-142.