Collaborative and Intimate Editorship: Lucie Stanton

Other than Samuel Ringgold Ward and James W.C. Pennington, the two official corresponding editors, the Aliened American had yet another more dedicated contributor. The author of “Charles and Clara Hayes” in the inaugural issue, Lucie Stanton, used her writing skills to enrich the contents of the newspaper. Nevertheless, it is difficult to measure how much of a contribution she might have made to the newspaper, because she was mostly hidden from public view while helping her husband publish the paper both at home and in the office. Stanton lived with William Howard Day in the mid-19th century, when women’s labor was barely noted and her presence in the public was considered inappropriate. Despite his financial failure and the tragic loss of their first two children, she must have helped him succeed to be an editor, lecturer, librarian, educator, and organizer for Black civil rights activism.

As the interactive map of William Howard Day’s collaborators shows, the Aliened American exemplifies a collaborative work of Black intellectuals in the mid-nineteenth century. For example, the paper introduces its contributors: “Among our regular contributors, we are permitted to name Rev. Amos G. Beman, of New Haven, Connecticut; Dr. Martin R. Delany, of Pittsburgh, PA., and a host of good and true men from among us in all departments of life; and others from our white friends, whom we need not now mention.” Although the editor remains quiet about Lucie Stanton, one of the contributors, Delany, did not fail to notice her ability as a writer. In The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852), Delany introduces her with other luminous Black leaders such as Henry Highland Garnet and Charles Reason in the chapter “Literary and Professional Colored Men and Women,” saying, “Lucy [sic] Stanton, of Columbus, Ohio, is a graduate of Oberlin Collegiate Institute, in that State. She is now engaged in teaching school in that city, in which she is reputed to be successful. She is quite a young lady, and has her promise of life all before her, and bids fair to become a woman of much usefulness in society.”[1]

Lucie Stanton was born to Samuel and Margaret Stanton, early Cleveland Black settlers, in 1831. Samuel Stanton owned a barbershop, after moving from the South to settle in Cleveland, then a village of 1,200 with a Black population of less than one hundred. When he died, Lucy, his first child, was only one year old. Margaret remarried her late husband’s business partner, John Brown, in 1834. He, free-born from Virginia, came to Cleveland in 1828, and built his business with other Black residents in the city. Brown was the proprietor of the barber shop in one of Cleveland’s finest hotels, the New England House, until it was destroyed by fire in 1854. He accumulated his wealth through real estate investments and became the wealthiest African American in Cleveland before 1870.[2]

John Brown used his wealth to promote the education of Black children and Black civil rights. He, alongside other prominent African Americans in Cleveland including John Malvin, actively participated in state and national conventions, representing Cuyahoga County and Ohio. He also served as an Underground Railroad agent. According to Lucie's recollection, his family hid thirteen fugitives at one time in the house. In 1841, John Brown assisted Malvin in posting a thousand-dollar bond to secure the release of captured fugitives.[3] When Lucie Stanton was once humiliated by a school district’s superintendent because of her color, Brown immediately established a school for Black children at his own expense, although Ohio law provided no public school funds for them until 1849. Day’s early success and fame in Cleveland might be possible because of Lucie and her step-father’s influence on the local Black community.

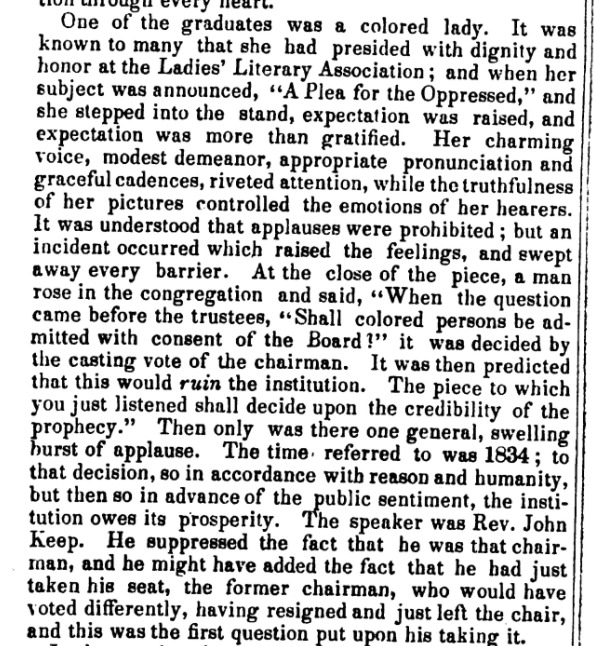

Lucie Stanton studied at Oberlin and was elected as a president of the Oberlin Ladies Literary Society despite some classmates’ opposition based on her race. She represented her class and delivered a graduation address, “A Plea for the Oppressed,” which was published in the Oberlin Evangelist on December 17, 1850. She taught in a Black school in Columbus where she emerged as a leader and organizer along with other Black women for the state conventions of Black citizens, in which Black leaders like Martin Delany witnessed great potential in her.

However, Stanton continuously faced racist and misogynic barriers both inside and outside Black communities. For example, in 1854 when both William Howard Day and Stanton applied for a joint membership of the Cuyahoga County Total Abstinence Society, only Day was admitted after the committee’s reconsideration of their application.[4] She also struggled to support herself and her child as a single parent. Their only child, Florence Nightingale Day, was just an infant when William Day abruptly abandoned his wife and child in 1859 during his trip to Britain for an antislavery fundraising and lecture tour. Although she granted his request for divorce in 1872, her letters for a job application reveal the challenges that a divorced woman experienced at the time when divorce was considered both a moral failure and a loss of Christian virtue, especially for women. The frequent change of her home address in the letters also suggests her financial instability. On June 26 in 1878, when she lived in Mississippi, she remarried Levi N Session, who was twenty years her junior. The couple moved to Loss Angeles later, and she founded the Sojourner Truth Home for girls in the city.

Despite her hardships, Lucie remained active in teaching and writing, and led a local Black community wherever she lived, including Jefferson, Mississippi and Los Angeles, California.

[1] Martin R. Delany, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852. Reprinted by Black Classic Press, 1993), 132-133.

[2] Bessie House-Soremekun, Confronting the Odds: African American Entrepreneurship in Cleveland, Ohio (Kent State University Press, 2009), 17.

[3] Ellen NicKenzie Lawson, The Three Sarahs: Documents of Antebellum Black College Women (Edwin Mellen Press, 1984), 190.

[4] Lawson, 196.