What the Editors Reprinted

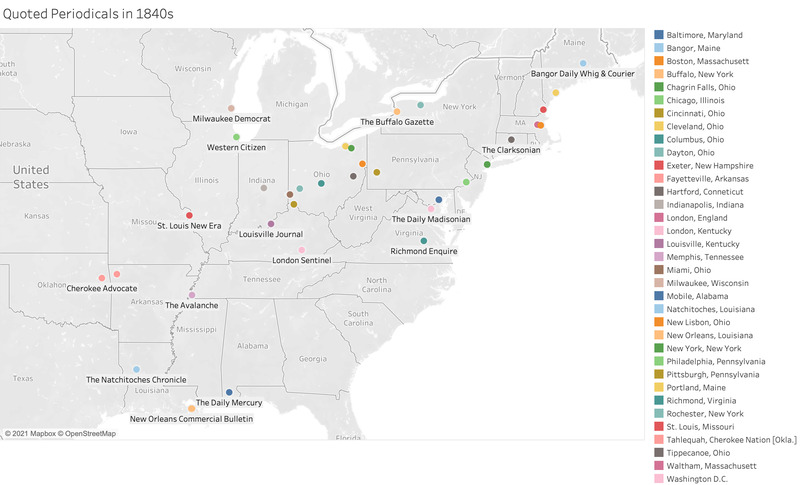

Reprinting pieces from other periodicals and published texts was a common practice in nineteenth century print culture. Many of Black newspapers did not have enough agents, correspondents, and resources to maintain profitable publications, relying heavily on other periodicals as alternative news sources for first-hand reports. In the case of the Black newspapers in this project, total 287 different periodicals were reprinted, quoted, or mentioned, often more than once, in sixty-five issues out of the fourteen newspapers. However, for Black editors, the reprinting practice was not merely a way of saving the cost of newspaper publication. It, rather, was a savvy editorial strategy to establish journalistic authority through direct and indirect conversations among printed materials. Data visualization about reprinted periodicals in the early Black newspapers of Ohio also invites us to spatial thinking in which we can imagine African Americans on the constant move literally and metaphorically to publish and circulate newspapers.

Even though a single issue of a newspaper is fated to be ultimately ephemeral and fragmented because of its time-sensitive nature and lack of wholeness, the practice of reprinting can reveal a coherent and enduring narrative that explains a larger context in which a newspaper was published. For this reason, Meredith McGill calls this practice “the antebellum culture of reprinting,” which helps us “recover . . . the vibrancy and importance of the literature that thrived under conditions of decentralized mass production.”[1] In other words, when we trace the periodicals that were reprinted in the Ohio Black newspapers in the nineteenth century, we can delineate a holistic picture of the Black press, which required their editors’ collaboration and conversation in the medium of periodicals. The reprinting practice strengthened the network among Black journalists and editors, and helped them identify a paper’s political and cultural role, so that a paper’s contents could be enriched to attract a broad range of readership. More importantly, any information about “what and when a periodical was reprinted where” can hint at the mobility that Black editors and agents achieved at the time when racism and institution of slavery limited African American traveling in the country.

Networks in Newspaper Culture of Reprinting

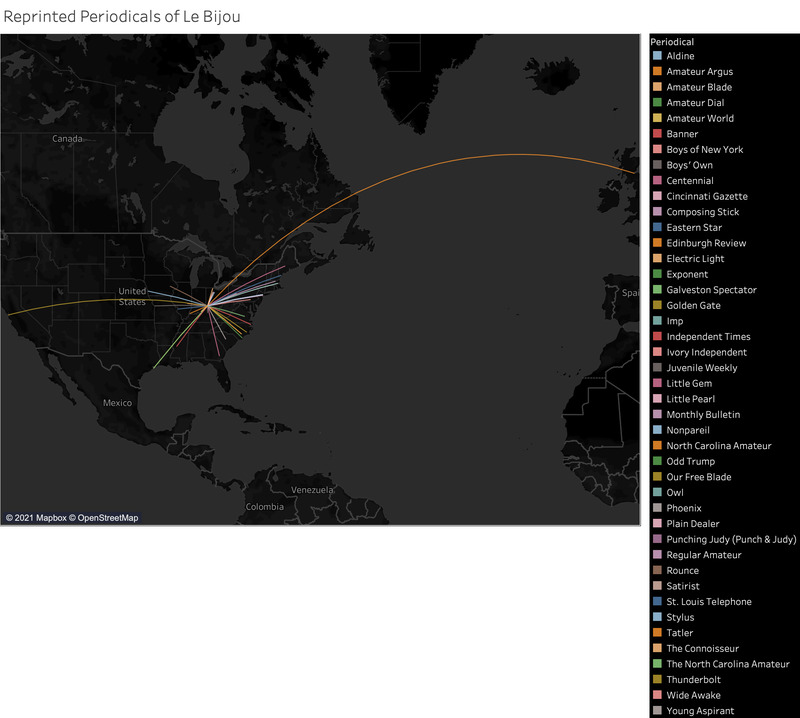

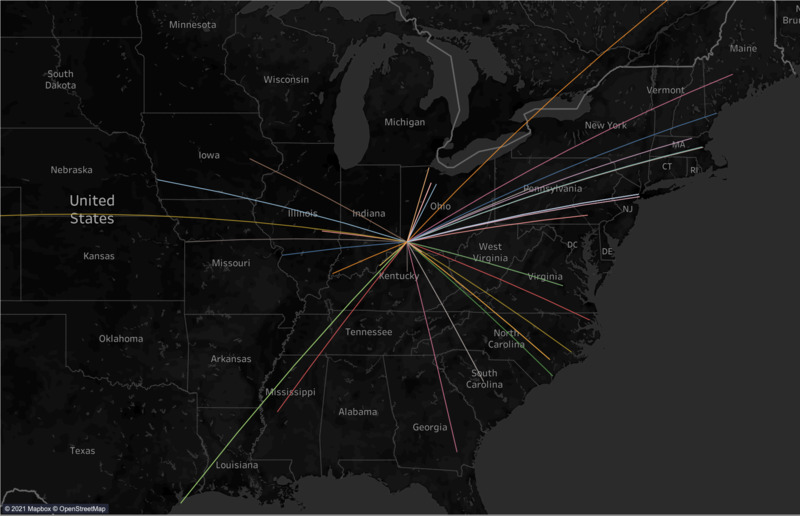

Textual relatedness among newspapers that reprinted one another in the nineteenth century formed a network, in which one newspaper engaged with collective reporting and writing. This network through the reprinting practice served dual roles: “as a means of recovering literal routes of circulation and transculturation, and as a metaphor for conceptualizing the cultural work of periodicals as they follow such routes,” according to Kelly Kreitz who explains the concept of network in the window of periodical studies.[2] For example, Herbert Clark’s Le Bijou uses numerous reprints from and comments on other contemporary amatuer newspapers with a long list of them in “Notes” of every issue. For its three-year run, the newspaper reprinted or cited at least seventy-nine different periodicals. Among them, we can see the London Telegraph (London, England) and San Francisco Wasp (San Francisco, California), both of which were published far from Cincinnati, the base of Le Bijou. The amount and geographical variety of the reprinted periodicals in Le Bijou evinced the editor’s engagement with a solid network of adolescent newspaper publishers, the National Amateur Press Association (NAPA).

Identity of a Black Newspaper

Reprinting an article from another periodical does not necessarily mean that a newspaper would agree with the political stance of a reprinted piece, just like “retweeting” is not always a Twitter user’s endorsement of a retweeted content in our modern world. Rather, in nineteenth-century newspaper culture, reprinting functions as an invitation to dynamic discussions, through which a newspaper could identify its own voice for readers. David Jenkins’ Palladium of Liberty (1843-1844) reprinted articles from at least sixty periodicals, and five of them were Black-authored newspapers including The Clarksonian, the first Black newspaper in Connecticut.

From the early of its publication, the executive committee of the Palladium of Liberty announced their decision on the paper’s direction that would be determined by democratic procedures for open discussion: “Still it is open for all communications, that may be sent in for publication. We will state our reasons for changing.—After consulting our friends and those that act with us in this matter, we were induced to alter our course.”[3] Therefore, the paper’s contents including reprinted articles resulted from the open conversation on what and how the Palladium of Liberty would serve as a Black-community newspaper.

The radical voice of the newspaper is a product of this participatory form of decision-making process. For example, the paper’s Black feminist voice is distinctive when it reprinted Martin Delany’s writing from The Mystery. He argues that Black women’s work outside home should be considered not disgrace but industry, criticizing any attempt to judge them in the same ideological frame of white womanhood: “Certain, we say, it is no disgrace, [for Black women] to live out, or to do any honest work for a living when necessity so compels us. . . . Yours is necessity, the young white lady’s is choice. She’s to blame, you are not.”[4] Subscribers’ letters and similar articles followed Delany’s defense of working Black women, suggesting their agreement with him. Later, the voice for Black women in the Palladium of Liberty emerged more explicitly, like one article that emphasizes the significance of women’s role in the Black community: “Female influence is now felt in all the relations of life since woman has been elevated to a proper station in society; her influence on individual happiness, and all prosperity is so good that every attempt to render it more beneficial is praise-worthy.”[5]

Reprinting through Framing

Reprinting part of another newspaper makes by no means a mere collage of various pieces from multiple writers and sources without a coherent control over that polyvocality. Reprinting, from citing a small part to reproducing an entire article, always requires an editorial intervention in any original text. Through this process, an editor allows readers to (re)read an original text from different perspectives while sending a subtle message on how to read that text. Sarah Salter and Jim Casey, who theorize the editing of ethnic newspapers as a complex mode of journalistic practice, argue that “the craft of editing is itself a distinct but long-running cultural mode in which editors could use the materials and formats of their publications as a means of layered expression and signification.”[6] Likewise, most editors of the Ohio Black newspapers in the nineteenth century maneuvered the ways of reprinting so that they could deliver their messages.

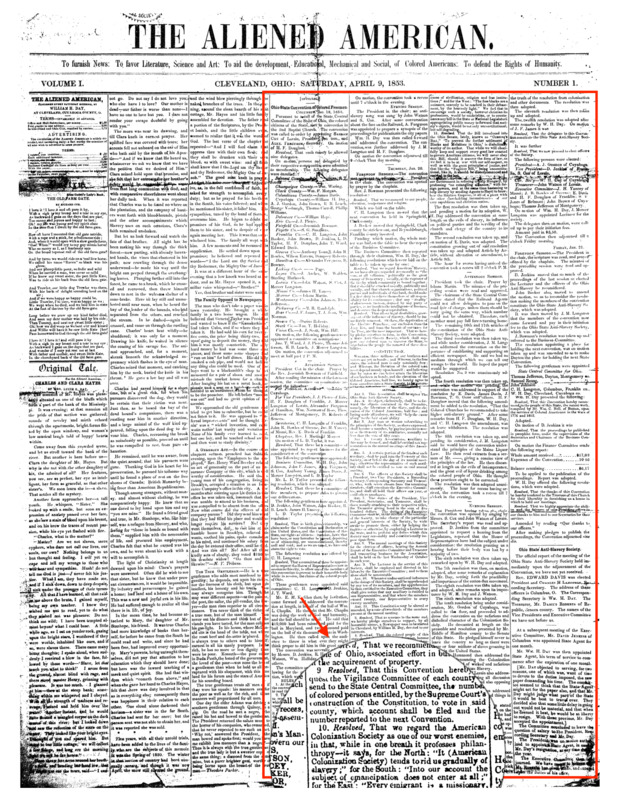

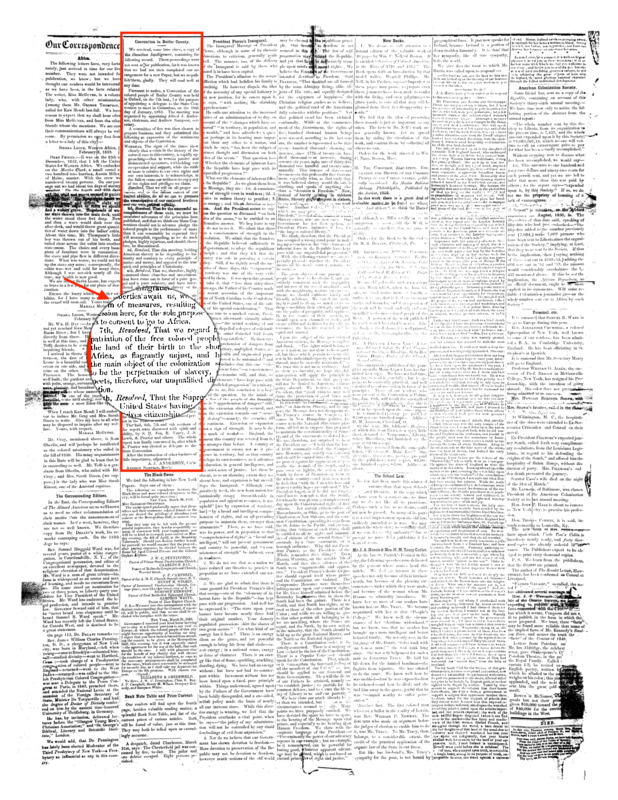

In its inaugural issue of the Aliened American, William Howard Day reprinted Proceedings of the Ohio State Convention of Colored Freemen, held in Columbus, on January 19th to 21st in 1853. And, he also published the meeting minutes of Butler County convention, in which the county members had prepared for the state convention about two weeks earlier. Readers with keen eyes could notice that none of Butler County attended the state convention despite their county-level discussion on what to present their resolutions there. Nevertheless, because both convention proceedings appeared in the same issue of the newspaper, readers were informed that, regardless of the absence of delegates from Butler County, their voice was heard at the state convention. For example, the eighth resolution at the county meeting states, “That we regard the expatriation of the free colored people from the land of their birth to the shores of Africa, as flagrantly unjust, and believe the main object of the colonization society to be the perpetuation of slavery, and it meets, therefore, our unqualified disapprobation.” Accordingly, the delegates at the state convention adopted this resolution: “10. Resolved, That we regard the American Colonization Society as one of our worst enemies.” This consistent voice against African colonization exemplifies the democratic process of decision-making from a grassroots level to a larger-scale one. By juxtaposing the state proceedings and county meeting minutes, the editor let the reader know not only about the echoed resolution at the convention but also about the multilevel participations of Black residents to reach that resolution. In doing so, Day portrayed Black Ohioans as democratic citizens, who formed a collective voice through democratic process.

And, Newspapers on the Move

Mobility in places is a prevailing theme in African American expression. Because a newspaper is printed and circulated to reach out to those who may live far from its publication site, the theme of mobility beyond socio-political boundaries set in geography appears significantly in the Black press. It is impossible to tell exactly how far a newspaper traveled, as in many cases it did not leave a trace. However, the reprinting practice among various periodicals offers a clue to tell part of a newspaper’s trajectory before its complete disappearance. For example, although no copies of the Disfranchised American survived, the paper’s existence is known because another contemporary newspaper, Palladium of Liberty, reprinted its articles.

It is unclear how editors of Ohio’s Black newspapers collected various periodicals that were at times from unexpected places like Australia and Singapore.[7] We can assume that agents would not only recruit subscribers but also shared with the editors periodicals that they could obtain from subscribers and acquaintances. The reprinting practice reveals physical and metaphorical moves that editors and readers of Black newspapers achieved in the nineteenth century when the white violence to circumscribe Black mobility routinely occured. Black newspapers actualized this mobility that could lead readers to a radical imagination of different places including a liberatory site, in which they might be able to exercise full citizenship.

The germinal nature of a newspaper content in the reprinting practice can be explained by Ryan Cordell’s concept of “virality.” According to him, “the system of newspaper exchanges produced a kind of feedback loop, in which texts circulated because of their perceived value to readers while that perceived value was often tied to a given piece’s wide circulation.”[8] Black editors of nineteenth-century newspapers were aware of this “kind of feedback loop” that would prove a circulated text’s value. For example, one New Hampshire paper found the Ohio Black newspaper, Palladium of Liberty, worth introducing to its readers, after a copy of the Liberty had made its journey to the former’s editors in that northeastern state. Correspondingly, David Jenkins obtained the Exeter and responded to its misrepresentation of his paper. The Palladium of Liberty quoted a snippet from “Items” in the Exeter to criticize its patronizing introduction:

In the Exeter (N.H) News Letter, of April 20th, we find under the head of “Items,” following: “A number of Negroes in Columbus, Ohio, have commenced the publication of a Weekly Newspaper.” We wonder if the editor has just found out that the “negroes,” as he calls us, are to always keep silence; we find too much to do in the elevation of our colored race. The editor seems to cast reflections on us in noticing our paper. Why not notice our paper in a respectful manner?[9]

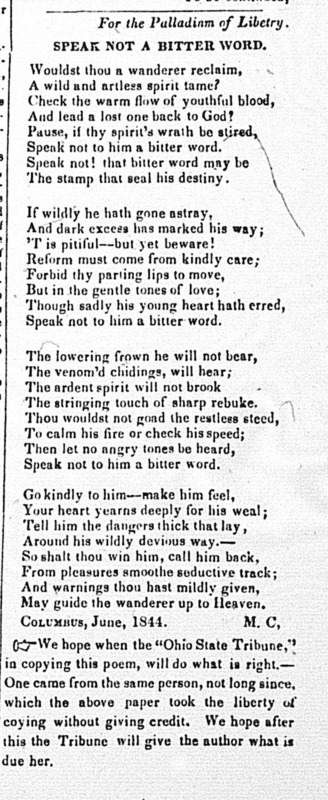

Another example of reprinting as a text-mediated dialogue is found in the same newspaper. On June 26, 1844, the Palladium of Liberty accused the Ohio State Tribune of reprinting the paper’s published poem without giving credit to its unnamed woman poet, underneath of her newly published poem: “We hope when the ‘Ohio State Tribune,’ in copying this poem, will do what is right.—One came from the same person, not long since, which the above paper took the liberty of copying without giving credit. We hope after this the Tribune will give the author what is due her.”[10] Pointing out the other paper’s unethical practice of reprinting, the editor not only highlighted the coveted value of his newspaper but also reaffirmed the unanimous woman poet’s authorship.

[1] Meredith McGill, American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 3.

[2] Kelley Kreitz, “Network,” American Periodicals: A Journal of History and Criticism, vol. 30, no. 1 (2020): 5.

[3] “Palladium of Liberty,” Palladium of Liberty, Wednesday, February 21, 1844, page 3.

[4] “Young Women: from The Mystery,” Palladium of Liberty, Wednesday, February 21, 1844, page 2.

[5] “Female Influence,” Palladium of Liberty, Wednesday, April 10, 1844, page 2.

[6] Jim Casey and Sarah Salter, “With, Without, Even Still: Frederick Douglass, L’Union, and Editorship Studies,” American Literature (forthcoming).

[7] The Rostrum reprinted a short article about the marriage of an European colonial official and native woman from the Singapore Free Press. “She Married the Hat,” Rostrum, May 6, 1899, page 3. And, The Afro American reprinted the Hobart Mercury’s article on the colony of Tasmania (currently, Australia) on September 19, 1885, page 2.

[8] Ryan Cordell, “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers,” published in May 2015.

[9] No title, Palladium of Liberty, May 29, 1844, page 3.

[10] “Speak Not a Bitter Word,” Palladium of Liberty, June 26, 1844, page 3.