William Howard Day, the Printer

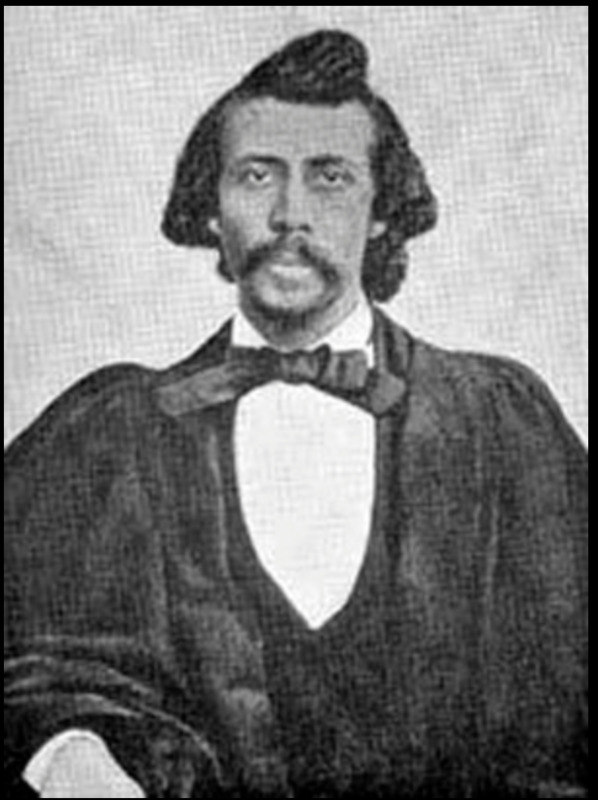

William Howard Day (1825 - 1900), the editor of the Aliened American, was born in New York City on October 16, 1825, the youngest of four children of John and Eliza Day. John Day was a veteran in the U.S. Navy of the War of 1812 where he served under Commodore Thomas Macdonough at the Battle of Lake Champlain. He also completed another tour in the Mediterranean Sea. He was honorably discharged on March 16, 1816.[1] John Day’s achievement inspired Day to organize the veterans jubilee in Cleveland on September 9, 1852, as a part of the Ohio State Convention of Colored Citizens.[2]

Day’s mother, Eliza, was a founding member of the first African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in the city. Because Eliza recognized the importance of education for her children, she enrolled her four-year-old son in a private school, the African Free School, No. 1, chartered by the New York Manumission Society and led by Levi Folsom, the school’s principal. The school grew to include several separate schools that provided an education to free, enslaved, and indentured Black youths in Manhattan.[3] When it was closed on May 1, 1834, William Day moved to a public school for Black students, where Ransom F. Wake was a principal. Day met his life-long friends and to-be Black leaders at these schools, including Charles Lewis Reason, Patrick Henry Reason, James McCune Smith, George Downing, Samuel Ringgold Ward, Isaiah George DeGrasse, Alexander Crummell, Henry Highland Garnet, and David Ruggle.

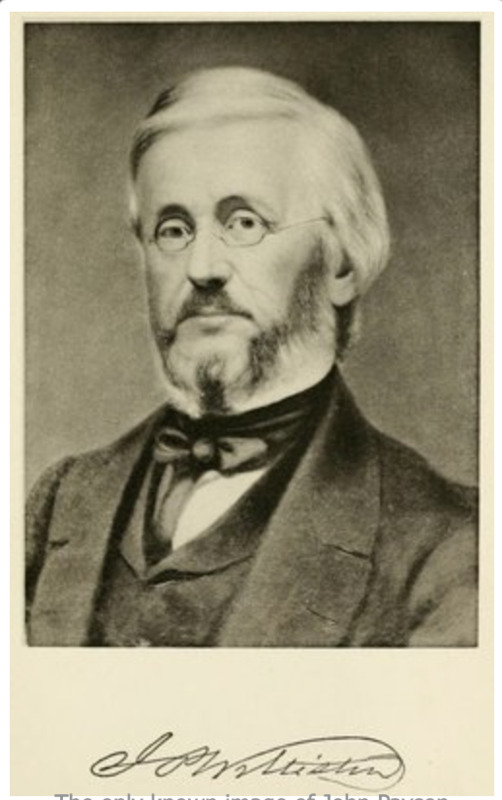

While thriving as an outstanding student at Reverend Fred Jones’s private Christian school at the age of twelve, Day met the Willistons who fostered his intellectual growth as a leader. John Payson and Cecelia Williston, who were affluent manufacturers (of silk and ink) and staunch abolitionists from Northampton, Massachusetts, offered Day’s mother to adopt Day, in 1838 after they witnessed his performance at a publicly staged examination. In Eliza’s agreement, Day resided with the Williston family for the next five years until he went to college.[4] They supported Day’s ambition for higher education. After his admittance was denied at Williams College because of his race, Day decided to study at Oberlin in Ohio. Oberlin College began to admit African Americans only two year after its founding in 1833, and became the second college in the U.S. to do so and is the oldest still existing. In the fall of 1843, William Day was the only African American student among the fifty students entering the first year of the College course.[5]

In addition to the Willistons’ substantive support for William Day’s education, they paved the way for Day’s printing career. On February 4, 1845, John Williston started his newspaper, the Hampshire Herald in Northampton by hiring Abijah W. Thayer (the former assistant editor of the Courier) as editor. During the five years of his stay with the Willistons, Day worked as a printer’s apprentice, most likely for the Northampton Courier. [6]

During his college years between 1845 and 1848, and probably until 1850 in Oberlin, William Day worked as a typesetter for the Oberlin Evangelist. The Evangelist was a biweekly newspaper that had been founded by four of Oberlin’s leading abolitionists and edited by J. M. Fitch. Day’s responsibilities included composing textual material onto a cast metal sort called a compositor’s clamp. Typesetting at that time was a tedious assignment--putting small engraved letters, or slugs, into a chase and then pounded them into place with a mallet. In considering the process, we may guess that it took him nearly five days to finish typesetting for one issue.[7]

Once he moved to Cleveland in 1850, William Day joined the Cleveland-based True Democrat and fulfilled various roles for the newspaper including a compositor, reporter, and editor to work with three other white editors. They were Thomas Brown (the newspaper’s owner), George Bradburn (a Boston-born politician and Unitarian minister), and John Champion Vaughan (a former enslaver from South Carolina and former editor of the Cincinnati Gazette).[8] The National Era praised the newspaper, saying “one of the ablest, most spirited, and plainspoken papers,” in the North.[9]

In 1852 , after meeting with the editors, Frederick Douglass also highly regarded the True Democrat as “the ablest Free Soil journal of the West," crediting it for being “terrible to doughfaces and demagogues of every description.” Douglass adds his first impression of Day:

I was happy to find William H. Day, (a young colored man of much promise,) employed in the office of the True Democrat. Mr. Day is spoken of as an exceedingly useful man, and is doing much to increase the respectability of his people.--The affectionate manner in which we heard him addressed by his white friends, was another proof to me, of the vincibility [sic] of prejudice against color. A few such young men as William H. Day, possessing talent, and devoting their energies to the elevation of the colored people, would soon destroy all disposition, on the part of our oppressors, to colonize us in Africa, or elsewhere. Such men are standing proofs of the capabilities of the whole race.[10]

Martin Delany was another prominent Black leader who noticed Day’s promising future in the same year when Douglass met Day. In his 1852 book, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, he introduces: “William H. Day, Esq., A. B., a graduate of Oberlin Collegiate Institute, is now in Cleveland Ohio, preparing for the Bar. Mr. Day is, perhaps, the most eloquent young gentleman of his age in the United States.”[11] Although William Day gained the two famous leaders’ attention to his career as an emerging editor and activist, he later diverged from both of them because of their differences in the issues of Black emigration, the U.S. Constitution, and politics.

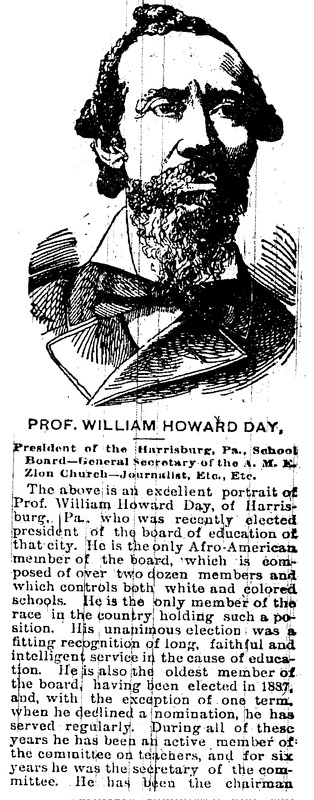

Even much earlier than Frederick Douglass discovered William Day, Day had already subscribed to Black newspapers such as Douglass's Paper and discussed his plan to publish a Black newspaper, tentatively titled The Voice of the Oppressed, in Ohio with Charles H. Langston. After his own two newspapers--Aliened American (1853-1854) and People’s Record (started as People’s Exposition, 1855-1856)--folded, Day continued to work for Black newspaper audiences. He served as a corresponding editor of Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s Provincial Freeman in Canada West between 1856 and 1857, and was an editor of the Zion’s Standard and Weekly Review (New York City) in 1866 and of Our National Progress (Harrisburg, PA) in 1870.

Participating in the national and state conventions to serve on various committees and representatives, Day also took responsibility of a recording secretary for printing and circulating a convention’s minutes and proceedings as a pamphlet or an article in antislavery and Black newspapers. At the convention above, for example, the final motion appointed Day to publish the minutes: “Resolved, That the printing of 500 copies of the proceedings of this Convention be given to Wm. H. Day of Lorain, and that he be requested to state the probable cost of such printing.”[12]

William Howard Day’s familiarity with print matters promoted him to be the first African American librarian in the Cleveland Library Association. The Association was established in 1848 to organize a Young Men’s Literary Association, which would provide opportunities for Cleveland residents and Western Reserve College (now Case Western Reserve University) students to appreciate literature such as a library, reading facilities, and lecture series.[13] Upon Day’s hire at the Association, the Plain Dealer criticized it for “throw[ing] itself into the arms of the Abolitionists.”[14] One year later, as the Catalogue of the Cleveland Library Association shows, Day proved that he could make an excellent librarian despite the racist prejudice against him. He must have left the position when his family moved to Chatham, Canada West in 1856.

The second Black newspaper in Cleveland----the Gazette, established by Harry Smith--eulogizes William Howard Day: “[W]hoever has read the doings of the race in the north the past quarter of a century has seen Prf. William Howard Day’s name among the worthies and always in a conspicuous place.”[15] A thorough biography of William Howard Day, Aliened American: A Biography of William Howard Day, was published by Todd Mealy in 2010.

[1] Todd Mealy, Aliened American: A Biography of William Howard Day 1825 to 1865, vol. 1 (Publish America, 2010), 63-64.

[2] Frederick Douglass Paper (Rochester, NY), October 1, 1852. Page 3.

[3] Ashton Gonzalez, Visualizing Equality: African American Rights and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 42.

[4] For more about John Payson Williston, see Chapter 3 “John Payson Williston: Abolitionist as Prohibitionist” in Bruce Laurie’s Rebels in Paradise: Sketches of Northampton Abolitionists (Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press, 2015).

[5] Gary J. Kornblith and Carol Lasser. Elusive Utopia: The Struggle for Racial Equality in Oberlin, Ohio. United States (Louisiana State University Press, 2018), 46-47.

[6] John Payson Williston shaped local newspapers with his financial power for the abolitionist cause. He persuaded the Northampton Courier “to introduce as much on the subject of slavery as . . . prudent . . . without endangering the pecuniary interests of the paper.” At the same time, he agreed to “endeavor to extend its circulation among the abolitionists” and pay the fee for an assistant editor. Hampshire Gazette (Northampton, NH), March 16, 1847.

[7] Mealy, 124.

[8] A. F. Callahan, “He was One of the Old Timers,” The Leavenworth Weekly Times (Leavenworth, Kansas), May 18, 1893, page 3.

[9] The National Era (Washington, DC), Jan. 15, 1852, page 2.

[10] "Jaunt to Cincinnati," Frederick Douglass’ Paper (Rochester, NY), May 13, 1852, page 2.

[11] Martin Delany, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852), reprint by Bibliolife DBA of Bibilio Bazaar II LLC (2015), 134.

[12] Cincinnati Gazette, February 2, 1849, quoted in State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio (1849 : Columbus, OH), “Minutes and address of the State Convention of the Colored Citizens of Ohio, convened at Columbus, January 10th, 11th, 12th, & 13th, 1849.,” Colored Conventions Project Digital Records.

[13] Mealy, 225.

[14] Plain Dealer, December 28, 1854.

[15] The Cleveland Gazette of March 19, 1898.