1860s: The Black Press during the Civil War

The 1860s in Ohio like other parts of the country experienced tumultuous changes caused by the Civil War. The Lincoln administration hesitated to authorize the recruitment of Black troops in the early of the War because of the concern that such a move would prompt the border states to secede. By mid-1862, the declining number of white volunteers and the increasingly pressing personnel needs of the Army propelled the government to pursue Black recruitment. In May 1863 the government established the Bureau of Colored Troops to manage Black soldiers, and the first authorized Black regiments were filled with volunteers from South Carolina, Tennessee, and Massachusetts. Although Ohio illegalized slavery, the state also strictly banned Black residents’ bearing arms in the white fear of Black revolt, and therefore they could not enlist the Army as an Ohio regiment. In the beginning, at least 158 Black Ohioans went to Massachusetts to volunteer at the 54th regiment, the first Black unit in the nation. John Mercer Langston--Oberlin graduate, long-time delegate at the Colored Conventions, Ohio’s first Black lawyer, Congressman, and founding dean of Howard Law School--encouraged Black Ohioans to enlist the Union Army alongside Frederick Douglass. In total, 5,092 Black Ohioans served in the United States Colored Troops.

The lack of journalists and resources during and after the Civil War resulted in the decreasing numbers of American periodicals. Black press was not an exception for this temporary decline, as Penelope Bullock argues that no Black periodicals established before 1865 survived the War. Nevertheless, one Cincinnati-based Black weekly--the Colored Citizen--not only survived the War but also thrived because it served as the “Soldier’s Organ” by exclusively reporting on Black soldiers. The newspaper’s tenacity during the turbulent mid-1860s and early 1870s hints at its editors’ strategic collaboration with local communities to keep Black subscribers informed. According to John T. Morris's "The History and Development of Negro Journalism," there was one more Cincinnati-based Black newspaper during this period, The Central Star. However, none of other records or extant copies of The Central Star are known.

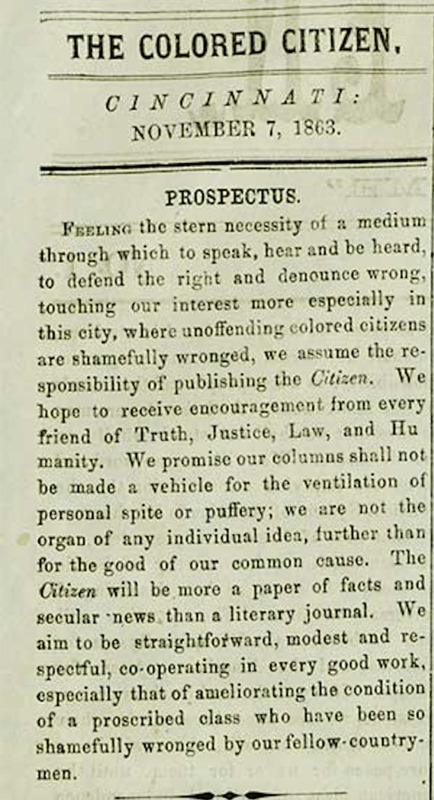

The Colored Citizen started on November 7, 1863 and is assumed to have continued until 1867 despite its occasional revivals in following years. In addition to the inaugural issue, only one more extant copy, published on May 19, 1866, is available. In its first issue, the newspaper introduced its editors and publishers as a collective, “the Cincinnati Young Men’s Literary and Publishing Company.” The other extant issue lists John P. Sampson as manager of the “Joint Stock Company,” instead of mentioning its editors and publishers. This reveals that the newspaper, like many other Black periodicals, was a product of communal work instead of an individual editor/publisher’s effort. The editorial collective included three generations of Black residents in mid-nineteenth-century Cincinnati.

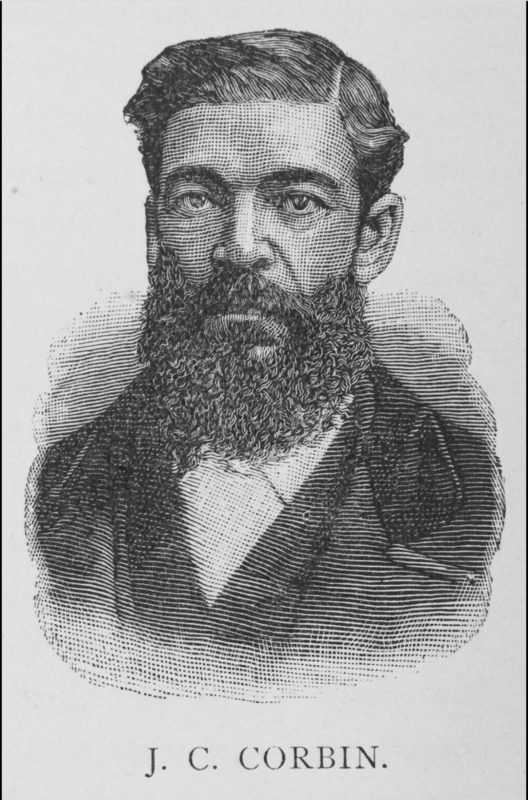

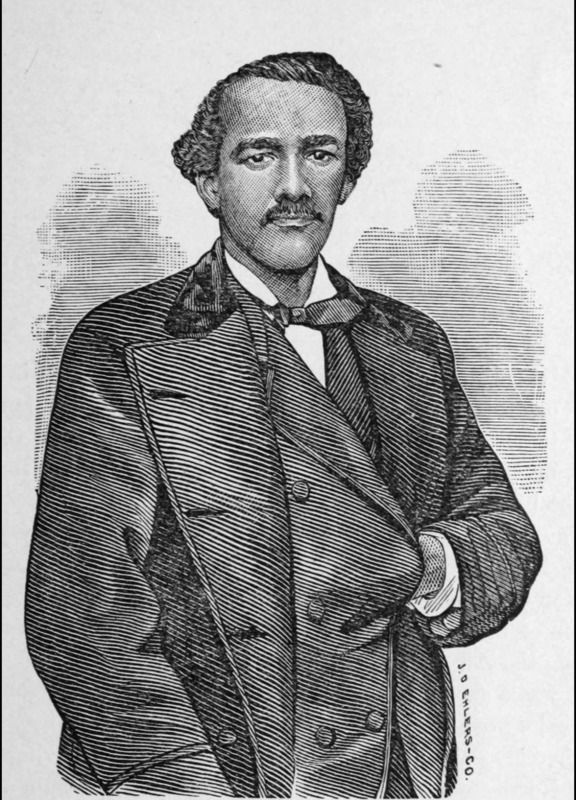

The two oldest members were William H. Yancy, a prosperous barber, and Reverend Thomas Woodson, allegedly the first son of Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings. Both of them were familiar with journalism prior to the Colored Citizen. Yancy offered crucial help to publish the Palladium of Liberty by forming its executive committee under David Jenkins’s editorship in 1843. Woodson also contributed to another newspaper, the Disfranchised American, as one of the six editors in 1844. With the substantial guidance of Yancy and Woodson, younger and well-educated editors including Joseph Carter Corbin and John P. Sampson practically oversaw the publication and circulation process of the Colored Citizen, at least until 1867 when the Cincinnati Commercial (March 30) praised the Colored Citizen. Young apprentice-type journalists also joined the newspaper. They were Charles W. Bell, Harry F. Leonard, and George Washington Williams.

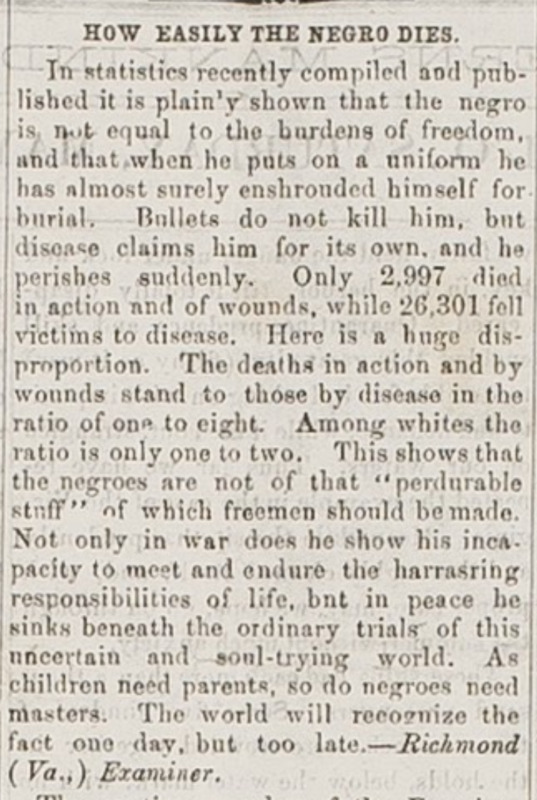

As its nickname,”Soldier’s Organ,” suggests, the Colored Citizen exclusively reported on Black soldiers. One article, quoted from the Richmond Examiner and titled “How Easily the Negro Dies,” included the numbers of fallen Black soldiers in the battle field, which were substantively higher than those of white soldiers. The article reads, “In statistics recently compiled and published it is plain’y shown that the negro is not equal to the burdens of freedom, and that when he puts on a uniform he has almost surely enshrouded himself for burial.” The newspaper also indicates that a Black community in Cincinnati vibrantly worked together to help children who lost their parents to diseases and the war. One notice in the 1863 issue calls for women who could donate sewing works for the benefit of Black orphans.

It is unclear when the Colored Citizen ceased. However, the editors tried to revive the newspapers several times. Charles Bell attended the first Convention of Colored Newspapermen in 1875 as a representative of the Colored Citizen, which had resumed publication after a two-year hiatus. Another editor, Harry Leonard also attempted to reissue the newspaper in January 1887, according to Lyle Koehler’s Cincinnati’s Colored Peoples. The Free American reported that the Colored Citizens finally "croacked" because of "a monetary complaint" in March 1887.