Paul Laurence Dunbar and the Dayton Tattler

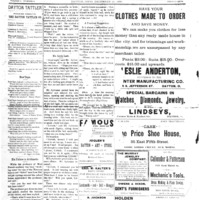

Paul Laurence Dunbar published the Tattler, Dayton-based Black newspaper, between 1890 and 1891. It says, “We will have items from the surrounding towns in subsequent issues. Those who are interested in news from Xenia, Springfield, Cincinnati, Columbus and other such cities may read the TATTLER and find it.” A team of the editors and agents--including Preston Finley, Chester B. Brody, Frank J. Mitchell, William Mason, and Val. W. Anderson--joined the Tattler under Dunbar’s leadership. It is unclear how much those editors and agents were involved with the publication process of the newspaper. The Dayton Tattler seemed to have circulated only for six weeks.[1] When Dunbar hadn’t finished his high school education yet, he started the newspaper to promote the interests of African Americans in Southwestern Ohio. Although their names are not listed in the newspaper, it is well known that the Tattler was printed by Dunbar’s classmate, Orville Wright, and his brother Wilbur, who later became famous for their invention of the airplane. As the editors and printers were able to publish the newspaper as long as financial resources were secured, the paper did not last longer than the short six-week period. The two extant copies--on December 20 and December 29, 1890--are available to our examination. A part of the inaugural issue, published on December 13, 1890, is also included in In His Own Voice: Dramatic and Other Uncollected Works of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, edited by Herbert Woodward Martin and Ronald Rimeau.

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s career as a newspaper editor hasn’t been studied well in comparison to his writing career as a poet. Nevertheless, the newspaper demonstrates the emergence of Dunbar as one of the prominent Black writers who paved the way for the Harlem Renaissance in the early twentieth century. He was familiar with the history of Black journalism, as he cited Freedom's Journal, the Ram's Horn, and the North Star.[2] Dunbar broadened the scope of the Black press to a vehicle for Black literary expression. In addition, the Tattler, differently from other contemporary Black newspapers in Ohio, targeted both Black and white readership without blurring its agenda for the elevation of Black Americans. Dunbar’s ability as an editor was evident when he edited The High School Times, a monthly publication issued by the pupils of the Central High School (later, Steele High School) where he was only one Black student among its twenty-eight members.[3] His closest friends were the printers, Orville and Wilbur Wright, who were from a progressive family. The Wright brothers kept Dunbar’s poem above the press on the wall of the print shop in about 1892:

Orville Wright is out of sight

In the printing business

No other mind is half as bright

As his’n is.[4]

On the inaugural issue, Dunbar insists that a Black newspaper discuss more than “one question, the race problem,” although it is important. The Tattler showcases “a variety” of writing about numerous subjects, instead of agitating readers for politics without actually taking action for change.[5] Even when any article reports on a political issue, its tone remains humorous and light. For example, pointing out the unfair taxation on Black citizens, one article reads: “You know well, that the Afro-American is not one to remain silent under oppression or even fancied oppression. When kicking is needed they know how to kick.”[6] In this way, Dunbar used the pages to publish his own versatile writings from prose to journalistic articles to poetry that thematize Black humanity beyond contemporary political discourses revolving around Black American citizenship.

His lesser-known early writings can be found in the Tattler, including “A Practical Suggestion,” “A Parrot Story,” and “The Gambler’s Wife.” At the same time, Dundar aimed at Black readers who could not but be interested in politics, as their political participation and votes were gradually considered significant: “The colored voters in the last election were very much like cats, when they were trampled upon, they turned around and scratched! Well it’s all in nature.” [7] After the Tattler ceased, Dunbar became an elevator operator in 1891. Only one year later, he joined the Western Association of Writers, voted in on the basis of the opening address he delivered at its annual meeting that year in Dayton. James Newton Matthews, a poet who attended the meeting, wrote his observation of Dunbar, which helped him find a publisher. As a result, Dunbar published his first volume of poetry in 1893.

[1] Fred Howard, Wilbur and Orville: A Biography of the Wright Brothers. (Dover Publications, 1998), 560.

[2] Matthew Teutsch, "Paul Laurence Dunbar, Racial Uplift, and Collective Identity," Black Perspectives (Feb. 2019).

[3] Paul Laurence Dunbar, The Life and Works of Paul Laurence Dunbar, edited by Lida Keck Wiggins. (J.L. Nichols & Company, 1907), 29. Smithsonian Libraries.

[4] Ivonette Miller, “Orville and Wilbur Wright: An Intimate Memoir," The Antioch Review, vol. 34, no. 4 (Summer, 1976): 452.

[5] Dayton Tattler, December 13, 1890. Qtd in In His Own Voice: The Dramatic and Other Uncollected Works of Paul Laurence Dunbar, edited by Herbert Woodward Martin and Ronald Primeau (Ohio University Press, 2002), 171-172.

[6] Dayton Tattler, December 20, 1890, page 2.

[7] ibid.