1870s: 2nd Generation of Black Journalism

Black Americans experienced a painful despair after a high hope for anti-racist justice in the U.S. They achieved that the three Amendments for Black civil rights were ratified by the beginning of 1870 so that they as citizens could participate in politics. However, they witnessed that the Reconstruction abruptly ended in March 1877 and the promises made by the government were abandoned. Black journalists in the United States actively began to publish periodicals right after the end of the Civil War, in order to empower their pen to educate and mobilize Black Americans when their political rights were continuously neglected by the federal and state governments. In addition, the rampant white violence against Black Americans, like the Ku Klux Klan and lynchings especially in the South, compelled them to assert their dignity and humanity in print. Just like early Black periodical editors used print to educate and build mutual aids for Black Americans, the need for periodicals in the 1870s seemed more urgent than any other period. John T. Morris, editor of the Cleveland Globe, summarizes the significance of Black press in this period:

“The beginning of the decade opens a period in the history of the race, in which the mind of the Negro began to study more closely his own condition as an American citizen; it was a period of kuklukism [sic], shot-gun policies, and all manner of political crimes against the Negroes of the South. It was a time when public sentiment was strong against them; a time when public attention to these crimes was to be demanded by the Negroes of the country; and not until the Negro press throughout the country had vigorously clamored against these political crimes, was there any definite action taken on the part of the general and State authorities to check them.”[1]

During this time period, Black editors in Ohio published at least four newspapers: Cleveland Globe (1864?-1884?), Declaration (1876-?), Southwestern Review (1878-?), and Le Bijou (1878-1880). The generational shift of journalists and editors characterizes the Black newspapers of Ohio in the 1870s. Before the Civil War, Black Ohioans fought for public education of Black students, civic participation, and fair rights to property and vote by organizing political rallies, conventions, and submitting petitions. As a result, their younger generation could benefit from educational and political opportunities that their elders had not had, while continuing the intergenerational activism for Black civil rights. Likewise, most newspaper editors in the 1870s had experienced working with the earlier generation of Black journalists and editors, keeping and enriching the tradition of the Black press.

One of the younger editors of the Colored Citizen, Charles W. Bell published the Declaration in Cincinnati in 1876 presumably right after folding the Citizen in the same year.[2] He was a graduate of the Cincinnati School of Design and served in the Cincinnati School System from 1868 to 1889. He also published columns, a prototype of the “Colored Notes,” in the Commercial Gazette. As he continued to work as a newspaper editor, Bell issued the Ohio Republican in 1892. Unfortunately, none of his papers’ extant copies survived for our examination.

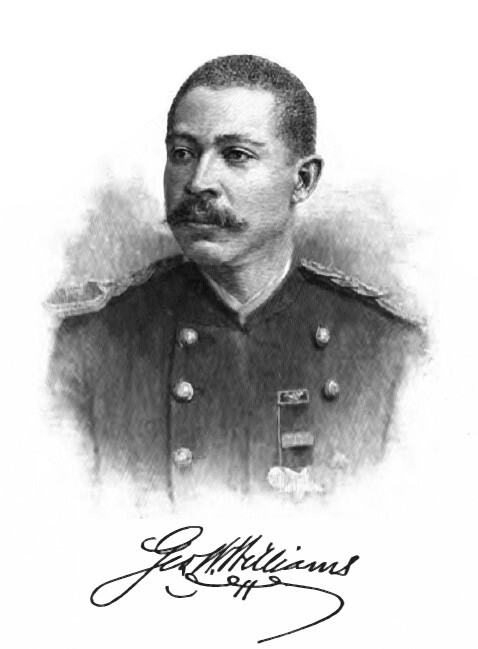

Another editor of the Citizen, George Washington Williams now as a stand-alone editor, issued the Southwestern Review in 1878. However, his contribution to the Citizen is unclear because his military service as a Union Army soldier and voluntary fighting on the behalf of the Mexican populace to remove Emperor Maximilian did not exactly coincide with the time of the publication of the Colored Citizen. After the Civil War, he studied at Howard University and in Newton Theological Institution. When he eventually moved to Cincinnati to study and practice law, he published the Southwestern Review as well. He also became the first African American elected to the Ohio legislature and served in the Ohio House of Representatives from 1880 to 1881. Williams published important Black history books including History of the Negro Race in America from 1618 to 1880 (1883) and A History of the Negro Troops in the War of the Rebellion, 1861-1865 (1888).

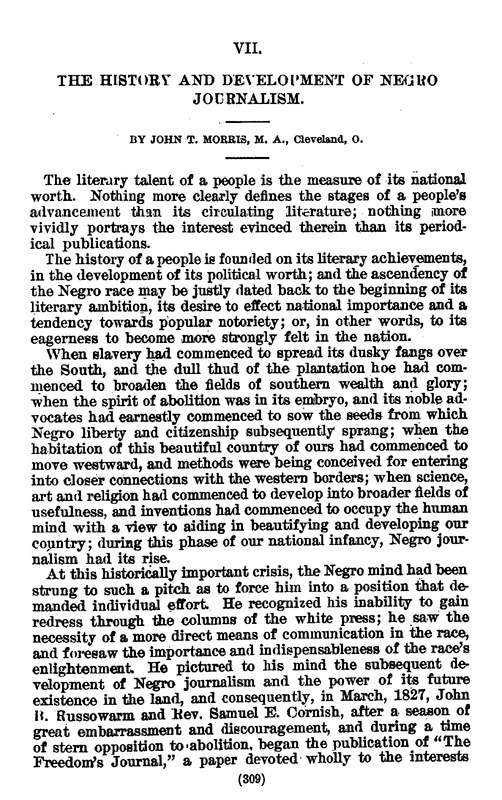

The Cleveland Globe was published by Richard A. Jones and John T. Morris from 1864 to 1884, according to James P. Danky and Maureen E. Hady in African American Newspapers and Periodicals (Harvard UP, 1999). Sara Fuller’s study, The Ohio Black History Guide (Ohio Historical Society, 1975) says that the newspaper was published between 1885 and 1890, but this estimation seems inaccurate. John Morris introduced his newspaper as one of the papers that appeared in the 1870s. He wrote "The History and Development of Negro Journalism," mentioning about the newspaper: "The Globe [was] published at Cleveland, Ohio, by R.A. Jones, Esq., battling for the cause. It was a time in the history of Ohio when Republicanism was hidebound, and every Negro who publicly protested against the political bossism that had so long ruled this State. . . . The Globe has been successful as an educator, and it stands today daring to proclaim the principles that underlie our success as a race."[3] No extant copies of the newspaper are known.

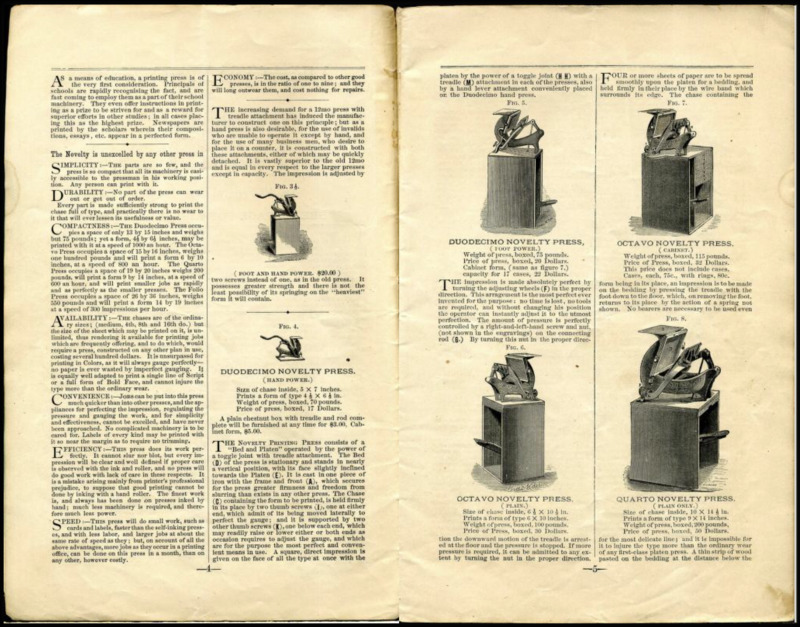

In addition to this political climate, the advancement of printing technology contributed to the increasing publications of periodicals in this period. In 1867, Benjamin O. Woods of Boston invented an inexpensive press, as he named it “Novelty Press.”[4] Although this press machine was not widely available to Black editors or useful for a broadsheet newspaper in comparison to white editors, it helped young and amateur Black journalists print their papers without too much cost of printing. In the 1870s, many amateur newspapers, or “juvenile papers,” were published and gained popularity beyond among their targeted young readers. John Morris in his essay introduces a Brooklyn(NYC)-based Black amatuer periodical, The Peoples’ Journal, which, published by Rufus L. Perry, had a circulation of over 10,000 subscribers. [5] Cincinnati-native, Herbert Clark (sometimes, “Clarke”) of Le Bijou was one of the amateur newspaper editors who gained national recognition beyond racial and regional boundaries. You can learn more about Herbert Clark and Le Bijou in the following page.

[1] Morris, “The History and Development of Negro Journalism,” in The A.M.E. Church Review, vol. 6, no. 3, in January 1890, 312.

[2] When Charles W. Bell attended the 1875 Convention of Colored Newspapermen, he represented the Colored Citizen. Convention of Colored Newspaper Men (1875 : Cincinnati, OH), “Convention of Colored Newspaper Men Cincinnati, August 4th, 1875, Wednesday A. M.,” Colored Conventions Project Digital Records, accessed September 9, 2021.

[3] John T. Morris, “The History and Development of Negro Journalism,” The A.M.E. Church Review, vol. 6, no. 3, in January 1890.

[4] “Amateur Newspapers,” American Antiquarian Society.

[5] Morris, 312.