1850s: Aliened American

In the 1850s, Black Ohioans’ efforts to publish their own periodicals continued, and, as a result, three newspapers appeared: Peter Humphries Clark’s Herald of Freedom (weekly, 1855-?) in Cincinnati, and William Howard Day’s Aliened American (weekly, 1853-1855?) and People’s Record (or, People’s Exposition; monthly, 1855-1856?), both in Cleveland. Despite their short lives, these continuous appearances of multiple Black newspapers prove the strength of early Black communities because a newspaper publication was always a product of their collective endeavor to achieve communal goals.

The 1850s started with the notorious Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made all Americans, in both the South and the North, subject to maintaining the institution of slavery. Against the government that had failed to demonstrate any promise for Black civil rights and democracy independent of the slavery-based economy, African Americans reinforced their collective power by expanding national and state conventions beyond the north-eastern states. Ohio held its first state convention of Black Ohioans in 1837, and by the time of 1859, the state hosted two national conventions (in Cleveland in 1848 and 1854), and held at least twelve conventions. Printing and circulating the convention proceedings were a significant part of Black community building. It is not coincidental that most of the Black newspaper editors like William Howard Day and David Jenkins also served as transcribers and printers of the convention proceedings. These print matters not only demonstrated the collective movement of Black Ohioans beyond the geographical convention sites but also were intended to educate Black settlers from nearby slavery states as citizens to engage in civic activities.

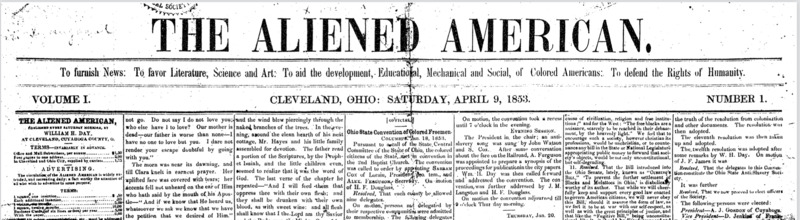

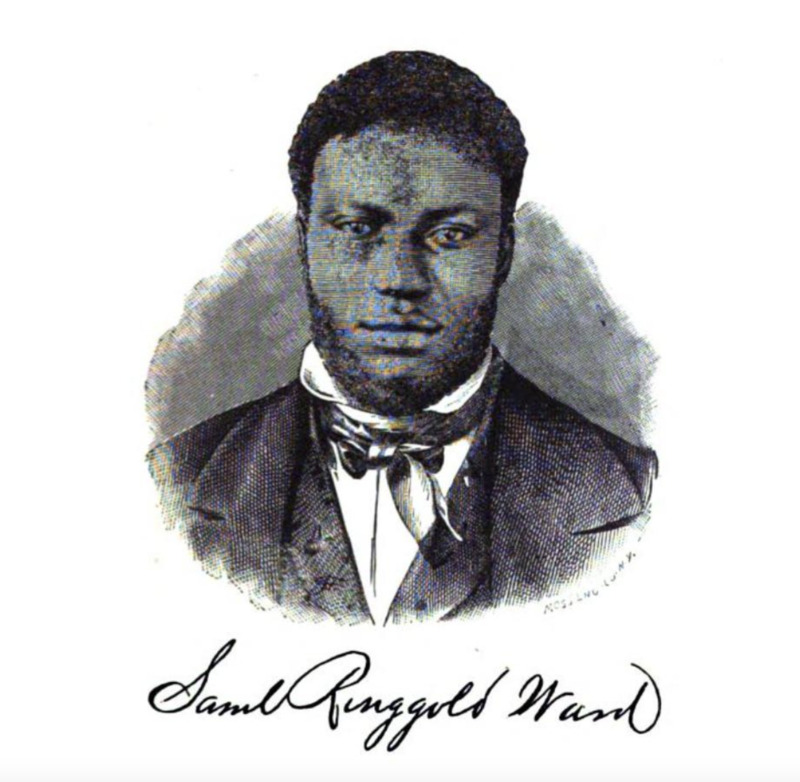

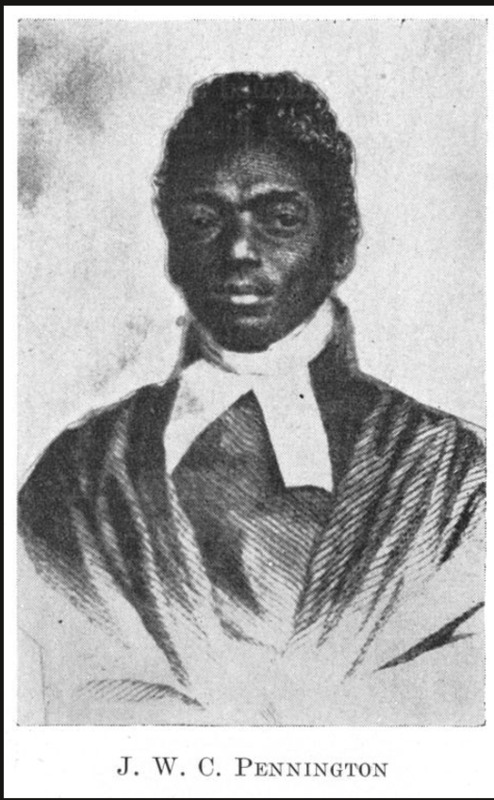

On Saturday 9th, April 1853, the first issue of the Aliened American was published in Cleveland. This weekly newspaper has four pages and each page consists of seven columns. This issue does not have any advertisements, but includes many potential advertisers, both Black and white business owners in northeast Ohio like Cleveland and Oberlin. Its motto reads, “To furnish News: To favor Literature, Science and Art: To aid the development, Education, Mechanical and Social, of Colored Americans: To defend the Right of Humanity.” It lists William Howard Day as a main editor, and Samuel Ringgold Ward in Toronto and Reverend James William Charles Pennington in New York City as corresponding editors.

William Howard Day and Charles H. Langston brought a plan for a Black newspaper at the 1851 State Convention of Colored Citizens in Ohio. Day introduced a proposal of the newspaper, named the Voice of the Disfranchised. It seems that Day decided to rename the newspaper Aliened American at this convention. Day met Reverend Joshua McCarter Simpson of Muskingum County--another Oberlin graduate, songwriter and singer, herbal physician, and Underground Railroad conductor. At the 1851 convention, Simpson presented multiple songs including “Liberia is Not the Place for Me.” Given that his song collection Original Anti-Slavery Songs was published in 1852, he might have sung one of his well-known “Song of the Aliened American” in the presence of William Howard Day. [1]

At last, at the 1853 Ohio State Convention of Colored Freemen, Day announced the imminent publication of the Aliened American and the delegates endorsed the newspaper: “We hereby pledge ourselves to support, by all honorable means, a Newspaper soon to be started in Cleveland, by William H. Day, devoted to our interests.” John Mercer Langston also added his continuous support for the Black newspaper, emphasizing the necessity of having a paper for Black Ohioans, if not Black (mid)westerners.

Although the Aliened American aimed at broad readership among Black Americans in the Midwest, securing sustainable subscribers from its beginning was challenging because of the small number of Black Ohioans in the 1850s. The 1850 census showed 224 Black residents living there out of 78,000 in Cuyahoga County, which was only 2% of the city’s total population. Even though, according to Bessie House-Soremekun, New Orleans was the only city that surpassed Cleveland in terms of Black property ownership and participation in a variety of occupations at that time, it was not enough to recruit a substantive number of advertisers and subscribers of the Aliened American.[2]

Accordingly, William Howard Day ambitiously looked for advertisers not only in Ohio but also New York, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Canada West. Unfortunately, Day did not expect another politically radical and local newspaper to come in the same year--the Cleveland Morning Leader (later, the Leader) began to publish just three weeks earlier than the Aliened American. Merged with the Forest City, the Leader emerged as a biggest news outlet for Free Soilers, abolitionists, and local residents. Its editor, Edwin W. Cowles, with whom Day must have collaborated once for the True Democrat, managed the paper to be the most popular local and progressive paper under the operation of E. Cowles & Company until 1885. As a result, Day had a hard time securing a sustainable subscription for the Aliened American and finally folded it before June in 1855.

Aliened American Engraved Head

The below emblem, made by Brainerd and Burridge--two Cleveland-based engravers--upon Day’s request for a specific design, shows two small Black children and their mother taking care of them while reading a paper at the table.

Oberlin Evangelist April 20 1853

The Oberlin Evangelist, where Day worked as a student at Oberlin, congratulated the newspaper’s publication: “The first number speaks hopefully for the talent and tact pledged for the support of this sheet; the name of the editor is alone a guarantee for a high standard of ability. . . . We hope that class of our citizens will not let this enterprise flag for lack of their patronage.” “The Aliened American,” Oberlin Evangelist, April 20, 1853, page 2.

People's Exposition

The annals of Cleveland do not reveal the exact date when the publication of the Aliened American ceased, but they show that Day started a new monthly publication, the Peoples’ Exposition, by June of 1855. On June 9, 1855, in her Provincial Freeman, Mary Ann Shadd introduced Day’s new monthly, with a slightly different name, People’s Record, praising its significance and early success.

You can learn more about William Howard Day, the editor, and Lucie Day (Stanton Sessions), his collaborator on the Aliened American in the following pages.

[1] For more about Simpson’s poetry, see Faith Barrett’s “Imitation and Resistance in Civil War Poetry and Song,” in A History of American Civil War Literature, edited by Coleman Hutchinson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 96-118.

[2] Bessie House-Soremekun, Confronting the Odds: African American Entrepreneurship in Cleveland, Ohio (Kent State University Press, 2009), 17-21.