1890s: Beyond Ohio

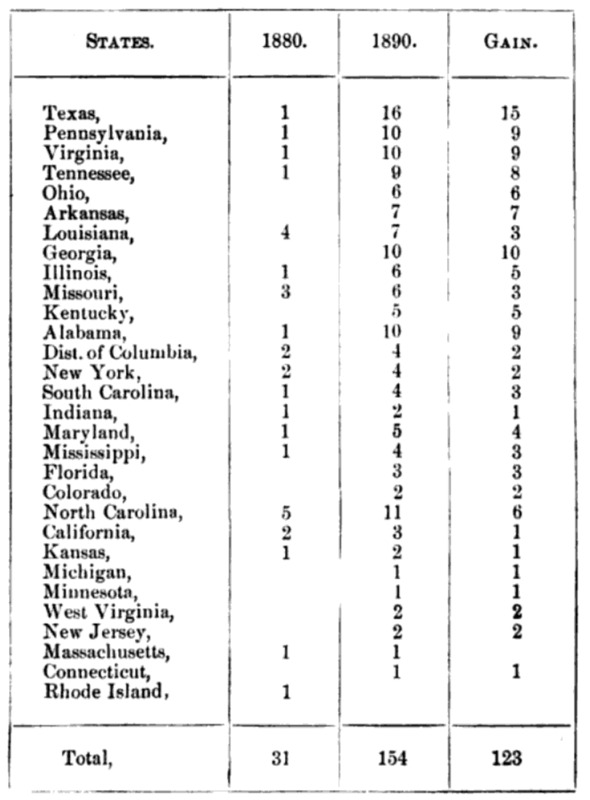

Black Ohioans published more newspapers in the 1890s than any previous period, demonstrating their continuously growing population and dynamic communities in the state. The 1890 census is the first for which there is aggregate data on Black employment in Ohio. In that year, of Ohio’s slightly more than 28,000 Black working men in addition to unestimated working force of Black women, approximately three-quarters were employed as laborers and service workers, while Black professionals made up about 2.4 percent of the total work force.[1] Their active contribution to the economy, education, politics, and culture led them to become substantial readers of Black newspapers. Although the Supreme Court reversed the 1875 Civil Rights Acts in 1883 and legitimized racial segregation through the Plessy v. Ferguson case in 1896, these decisions sparked public discussions and protest among Black Americans. They were keenly aware of the importance of their civic engagement in every sector of the U.S. society. Black leaders channeled Black political and cultural power through periodical publications.

The boom of Black newspapers in the 1890s was not limited to Ohio. Encapsulating the expansion of the Black press in its publications and circulations, the young educator and editor of Virginia, I. Garland Penn published his comprehensive study of African American journalism in 1891, The Afro-American Press and Its Editors. He starts Preface by characterizing the Black press:

In preparing this work on the Afro-American Press, I am not unmindful of the fact, that while I pursue somewhat of a beaten road I deal with a work which has proven a power in the promotion of truth, justice and equal rights for an oppressed people. The reader cannot fail to recognize some achievement won by that people, the measure of whose rights is yet being questioned, and will readily see that the social, moral, political and educational ills of the Afro-American have been fittingly championed by these Afro-American journals and their editors. Certainly, the importance and magnitude of the work done by the Afro-American Press, the scope of its influence, and the beneficent results accruing from its labors, cannot fail of appreciation.

The frequent number of Black press conventions indicates the significance of Black-published periodicals to African Americans in the late 19th-century, as Penn calls “the greatest stride.”[2] The National Convention of Colored Newspaper Men was held, presumably for the first time, in Cincinnati, in 1875. Black journalists and editors continuously had regular meetings, as proved by the remaining records including the following years and cities in which the conventions were held: 1880, Louisville, Kentucky; 1882, Washington, D.C; 1883, St. Louis, Missouri; 1886, Atlantic City, New Jersey; 1887, Louisville, Kentucky; 1888, Nashville, Tennessee; 1889, Washington, D.C.; 1891, Cincinnati, Ohio; and, 1894, Richmond, Virginia. Even though the full proceedings of all the conventions did not survive, this frequency reveals that Black journalists and editors built organized collaboration to publish the Black press. In addition, Black women journalists became gradually outstanding, after their invisible labor behind Black male editors had been barely remarked in print. In Penn’s The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, nineteen Black women in journalism are introduced including Ida B. Wells and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Even though none of them worked for a periodical in Ohio, the state at the same period had those who opened a door for Black women journalists of the following generation. For example, the entire local writers for the Columbus Standard consisted of Black women--Mrs. Buckner, Miss R. Monmouth, and Mrs. A. J. Chavers. In 1928 Florence W. Oakfield of the Columbus Voice could become the first Black newspaper editor in Ohio, as a result of the long tradition of Black women’s engagement in journalism.[3]

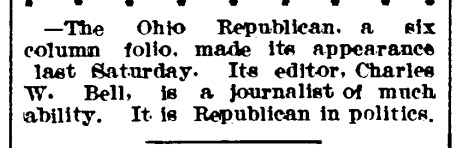

Ohio Republican (1892)

Charles W. Bell published the Ohio Republican in 1892. This is Bell’s third newspaper that he worked for as an editor. He published the Colored Citizen from 1863 to probably 1876, and the Declaration from 1876. Detroit-based Black newspaper, Plaindealer, once mentioned the Ohio Republican in an article, "The Ohio Republican" on September 23, 1892: “The Ohio Republican, a six column folio, made its appearance last Saturday. Its editor, Charles W. Bell, is a journalist of much ability. It is Republican in politics.” When Bell attended the 1875 National Convention of Colored Newspaper Men in Cincinnati, some other journalists questioned his qualification to represent the Colored Citizen because of its unsteady publication. But, he insisted on the importance of the meeting’s common interest in Black journalism. Most likely, he continued to attend the convention of Black journalists at least by the time when he published the Ohio Republican, as it was recognized by other Black periodicals. It is unclear when the newspaper folded. No extant copies are known.

Cincinnati News Recorder (1894-1895?)

The Cincinnati News Recorder was published by James S. Sandipher, first on Monday, January 1, 1894, with the motto: “A Weekly Newspaper, Published in the Interest of the Colored Race.” Sandipher had eight associate editors including Bedford Williams. While promoting the interest of Black readership, Sandipher clarifies that the paper “do not give any political news or political opinions, we publish the news for all political factions alike” in its inaugural issue. This statement reflects the political tension within Cincinnati’s Black communities who were divided over political issues and parties. The newspaper office was located in the Sumner House, a successful Black-owned lodging house at 296 and 298 W. Fifth Street. This indicates that the newspaper was sponsored by Black business owners, whose advertisements appeared on the paper. However, the other extant copy a year later does not have the advertisement, and the paper changed from a four-page to a two-page paper, insinuating its financial precarity without a sponsor. The newspaper, if not political, was religious, as it reported on religious activities and messages. Sandipher’s daughter-in-law, Louise Sandipher, is I. Garland Penn’s daughter. She contributed the current extant copies to the Cincinnati Historical Society Library.[4] It is unclear when the newspaper ceased.

Voice of the People (1896)

The Cincinnati-based weekly, Voice of the People, was published by Samuel B. Hill and Harry F. Leonard in 1896, according to the Cincinnati Historical Society Library’s 1970 Bulletin (vol.28, no.4). Wendell P. Dabney also introduces the Voice of the People, which “dwelt with us a while,” in his book, Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens.[5] Unfortunately, its copies did not survive for our examination. Samuel B. Hill was born in Xenia, Ohio, in 1862, and became a teacher. In 1884, Hill accepted the job of heading up Lockland public schools in Cincinnati. His political career started as a clerk in the office of the Cincinnati auditor until 1893, and in the same year, he was elected to the Ohio Legislature. In collaboration with Harry C. Smith, editor of the Cleveland Gazette, Hill helped the anti-lynching law passed.[6] Another editor, Harry F. Leonard worked for the Colored Citizens in the 1860s before co-editing the Voice of the People with Hill. His biographical information is barely available.

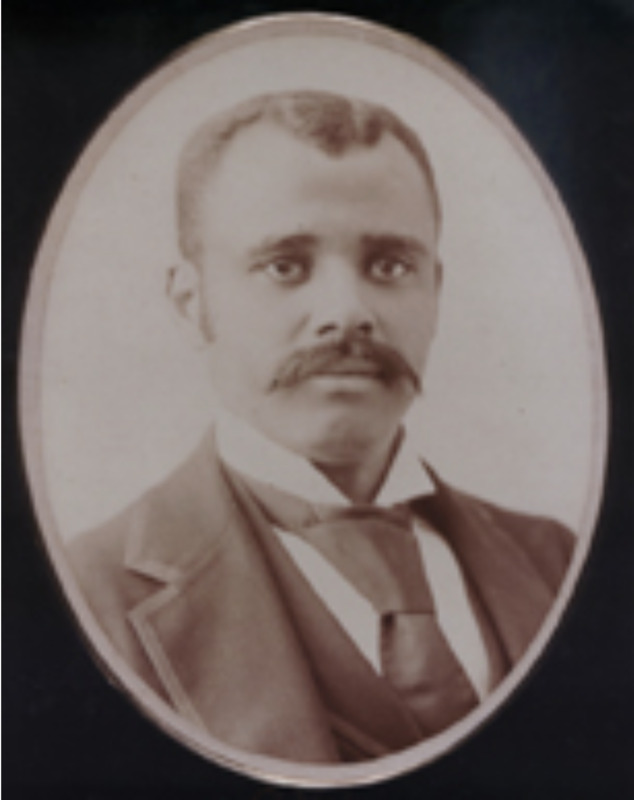

Republican Vindicator (1897)

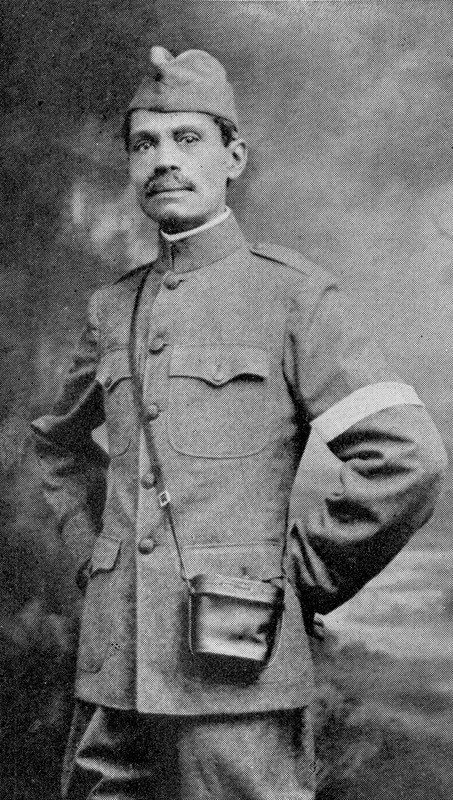

Ralph W. Tyler published the Republican Vindicator, a Columbus-based weekly newspaper, in 1897, with a motte, “Devoted to the Interests of the Negro Race.” Tyler (1860-1921) was a journalist, war correspondent, and government official. His career as a journalist is remarkable. The Cleveland Gazette reported that he used to work for the Afro-American and Free American, which is not confirmed by any other sources.[7] He wrote for the Evening Dispatch and Ohio State Journal of Columbus, while publishing the Republican Vindicator. In the early 20th century, he expanded his career by writing for the Colored American Magazine and poetry for Alexander’s Magazine, and by editing the Cleveland Advocate and Columbus Ohio State Monitor. During World War I, he was known to be the only accredited Black foreign correspondent, who reported specifically on African American servicemen stationed in France.[8] Only one issue of the Republican Vindicator on November 19, 1897, is available. The paper includes various local news and advertisements. Interestingly, the paper also contains a political caricature, which appeared most likely for the first time in the Black newspapers in Ohio. Its ending date is unknown.

The Informer (1897-1925?)

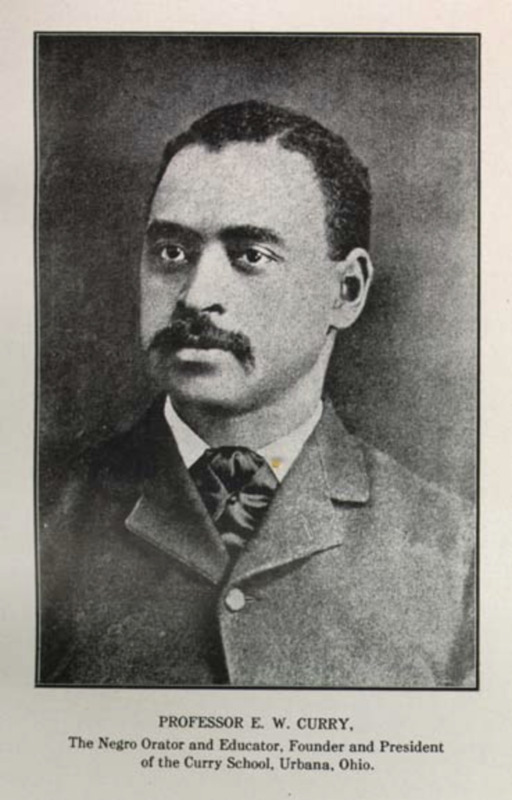

The Urbana-based monthly Informer was published by Elmer W.B. Curry in 1897, to serve as a forum for the editor’s views on African American Baptist Church, Black education and advertisement of his school’s work. The Informer includes various images, mainly as a result of the advancement of printing and photographic technology. Curry was a Baptist minister and educator in addition to his career as an editor. Born in Delaware, Ohio, in 1871 and educated in its public schools and at Ohio Wesleyan University, Curry founded the Curry School, an African American trade and normal school, in his hometown in 1889. When the school moved to Urbana in 1895, it was incorporated as the Curry Normal and Industrial School, also known as the Curry Institute. The School received a gift of $2000 from Martha Fouse, a formerly enslaved person, in 1913.[9] The institute resembled Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee in its emphasis on practicality in the labor market. Once the Informer asserts that “Nothing is taught that does not have a bearing upon actual everyday life.”[10] The ending date of the Informer is unclear. No copies published before 1900 survived, but this project hosts two of the later issues as example. However, the paper has been relatively well preserved at the Ohio History Connection, as it was published by the famous educator at his established institution until the early twentieth century.

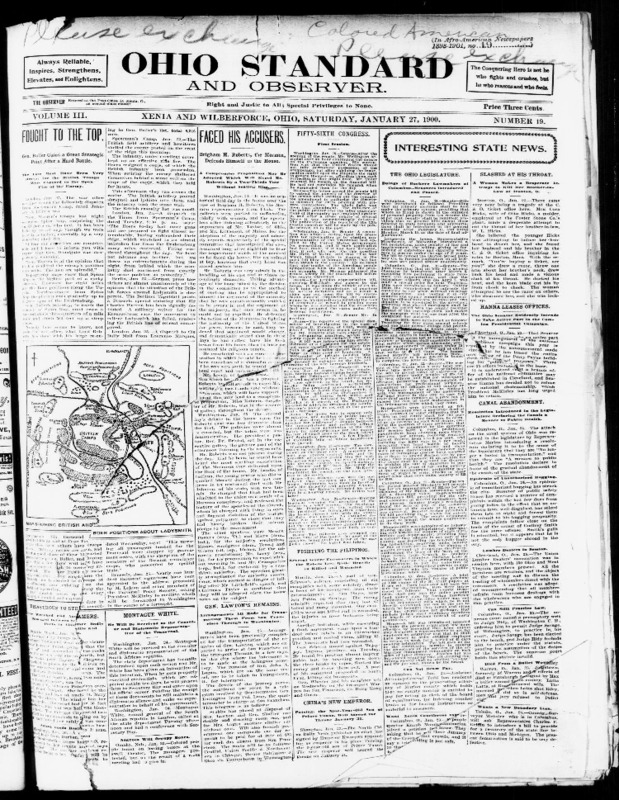

Ohio Standard and Observer (1897-1900?)

The Ohio Standard and Observer was published weekly in Xenia and Wilberforce, Ohio, starting in 1897. Its publisher was the Standard Publishing Co. in which Jordan Robb served as a president, John W. Leach as a vice president, W.S. Rogers as a secretary, and Dr. H.R. Hawkins as treasurer. The paper’s editor and manager was a local pastor, D. H. V. Purnell. The newspaper also had a solid team of ten contributing staff members: Bishops B. F. Lee, B. W. Arnett, Professors. T. D. Scott, George F. Woodson, Joseph P. Shorter, W. S. Scarborough, President S. T. Mitchell, Dr. J. M. Townsend, Dr. L. M. Haygood, and Reverend T. L. Wilson. Reflecting the vibrant teamwork of the editor and contributors in their tight-knit Wilberforce University community, the content of the Ohio Standard and Observer covered a broad range of domestic and international politics, education, local news, science, literature, and advertisements. Their motto was “Right and Justice to All; Special Privileges to None.” One copy survived: Vol. 3, no. 19, on Saturday, January 27, 1900. Its ending date is unclear.

Rostrum (1897-1898?)

The Rostrum was published by William L. Anderson as a weekly newspaper in Cincinnati, Ohio. The paper’s political voice is explicit, as one motto of the remaining issues reads: “The Rostrum is an Enemy of Racial Discrimination.” Although the life of the Rostrum was short, Anderson’s career as a newspaper editor and writer lasted throughout his life. He worked as a young apprentice and reporter for Charles P. Taft’s Cincinnati Times-Star in the 1880s, and was also a protege of Lafcadio Hearn to become a writer and poet. In 1901, he was the first and only African American member of the Typographical Union. Later, he also edited The Pilot, with nine other editors and correspondents, around the year of 1907 when Wendell Dabney’s Union began to publish.[11] For twenty-four years, Anderson operated a printing business, the only Black-owned printing facility in Cincinnati, while editing and publishing a number of newspapers, pamphlets, reports, and books.[12] Two copies of the Rostrum are available today: February 12, 1898, and May 6, 1899. The ending date is unknown.

Columbus Standard (1898-1901)

The Columbus Standard was published by Pearl William Chavers, as a weekly, beginning in 1898 and ending in 1901 when it was renamed The Ohio Standard World to cover Dayton, Cincinnati, Toledo, and Springfield in Ohio. He worked with J. M. Riddle, City Editor, and three local writers, who were Mrs. L. F. Buckner, Miss R. Monmouth, and Mrs. A. J. Chavers. It is notable that the writers and correspondents consisted of all Black women including the editor’s family member. The only extant copy on July 27, 1901, ambitiously announced that “over 21,000 people” read the paper, and it was “Ohio’s leading Afro-American Newspaper.” At the 1900 Republican National Convention, Chavers met Booker T. Washington, who he had admired. Following Washington’s “self-made man” ideal, Chavers used the Standard to promulgate his message for Black business development, voting rights, and industry. The paper also reported significantly on white violence against Black people. Chavers’ career as a newspaper editor did not last long, but he continuously endeavored to help urban Black residents. Chaver established Columbus’s Lincoln-Ohio Industrial Training School in 1907 to provide young Black women with practical training in domestic and industrial fields.[13] In 1905, he founded a women’s garment factory in Columbus, and moved it to Chicago in 1917. He also started the first nationally chartered Black bank, the Douglass National Bank in 1922. It is barely known that Chavers framed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) by introducing HR 8977 to the 68th Congress through Representative T. A. Doyle of Illinois in 1924.[14]

[1] David A. Gerber, Black Ohio and the Color Line 1860-1915 (University of Illinois Press, 1976), 61, 91.

[2] I. Garland Penn. The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, 1891. Reprinted by Arno Press, 1969, pp. 114.

[3] According to Lucius E. Lee, the Voice was “one of the first significant newspaper ventures for colored Columbus.” Lee, “Mrs. Florence Oakfield, Newspaper Pioneer, Was, And Is, Unusual Person,” Ohio Sentinel, Saturday, December 8, 1956. Columbus Metropolitan Library.

[4] Mae Najiyyah Duncan, A Survey of Cincinnati’s Black Press & Its Editors 1844-2010 (Xlibris, 2011), 23.

[5] Wendell P. Dabney, Cincinnati’s Colored Citizens: Historical, Sociological and Biographical (Dabney Publishing Company, 1926), 190.

[6] “Samuel B. Hill,” Ohio State House.

[7] “Ralph W. Tyler,” Cleveland Gazette, August 8, 1891.

[8] Alfred Lawrence Lorenz, “Ralph W. Tyler: The Unknown Correspondent of World War I.” Journalism History, vol. 31, no. 1 (March 2005): 2-3. This article investigates Tyler’s life-long career as a Black journalist.

[9] “Community Matters: A Voice of, by, and for the People of Delaware, Ohio,” vol. 5, no. 1 (July 2019).

[10] Informer, July, 1903. Quoted in David A. Gerber’s Black Ohio and the Color Line 1860-1915 (University of Illinois Press, 1976), 394. For more about the Curry Institute, see Curry’s A Story of the Curry Institute, Urbana, Ohio: 1889-1907. HathiTrust.

[11] Dabney, 202. No extant copies of the Pilot are available.

[12] Ibid., 355.

[13] Gerber, 392.

[14] For more about his life, see Madrue Chavers-Wright’s The Guarantee: P.W. Chavers, Banker, Entrepreneur, Philanthropist in Chicago’s Black Belt of the Twenties (The Wright-Armistead Associates, 1985).