1880s: Renaissance of the Black Press in Ohio

Black newspapers significantly grew in the number of them perhaps five-fold in the 1880s throughout the U.S.[1] According to I. Garland Penn’s The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, for example, Texas began with one and a decade later had fifteen, Georgia went from none to ten; Pennsylvania, Virginia, and Alabama each added nine to their original one publication. In 1880, Penn calculated, there were thirty-one publications; at the end of the following decade 123 newspapers had been added, for a total of 154.[2] There must have been more newspapers unnoticed by Penn, but many of the 1880s newspapers did not survive to 1890.

This explosive growth of Black periodicals happened because of the gradual advancement of Black Americans’ educational, economic, and political status. Like the previous decade, the Black Americans were becoming better educated as a result of their and earlier generation’s fight to offer public schools and to open the door of higher education. The broader educational opportunities for them led to more capable editors and sustainable subscribers of a periodical. And whereas the earlier Black newspapers suffered from financial difficulties, they now had various financial resources including middle-class and wealthy subscribers and sponsors. As a result, the Cleveland Gazette lasted more than sixty years, becoming the longest surviving Black newspaper in Ohio to today. Likewise, politically sponsored publications like the Afro-American in Ohio aimed at Black Americans who now had a right to vote because a periodical still functioned as a powerful medium to influence the public. Of course, printing tools were developed for low-cost and time-saving publication, in addition to the expansion of transportations that expedited newspaper circulations.

At least six Black newspapers including one long-lasting one into the twentieth century were published between 1880 and 1990 in Ohio: Afro-American (1882-1890?), Colored Patriot (1883-1884?), Plaindealer (1883-1895), Columbus Free American (1887-1888?), Dayton Tattler (1890-1891), and Cleveland Gazette (1883-1945).

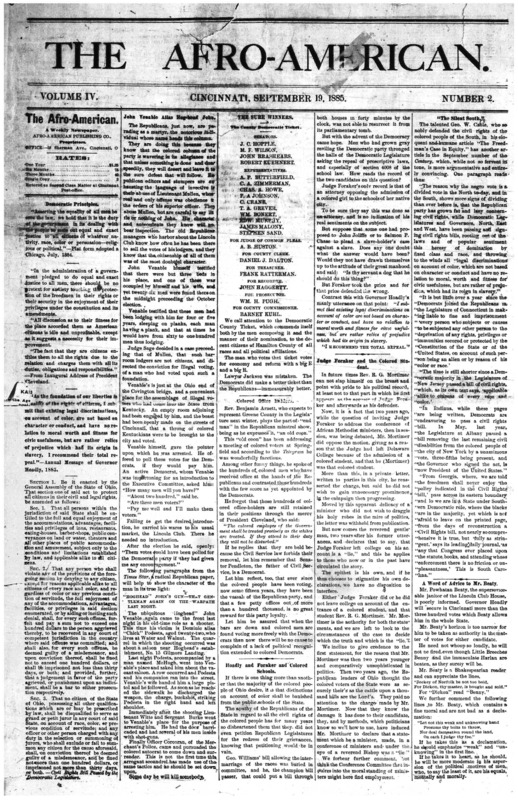

Afro American (1882-1890)

Peter H. Clark and his son, Herber Clark published the Afro-American, a weekly in Cincinnati. For his socialist ideals, Peter H. Clark steered his political direction from the Republican to the Democrats, which barely received Black support at that time. The Cincinnati Democrats appointed his son, Herbert Clark, to be a deputy sheriff, and financed their newspaper that appeared only during election campaigns. The Clarks asserted the danger of Black reliance on one party only through the newspaper, contrasting most Black Americans’ strong support for the Republican party. Peter Clark also served as an alternate delegate to the Democratic National Convention of 1884 to endorse Democrat Grover Cleveland for president. Although the Afro-American explicitly promoted its political agenda and was published seasonally, other Black newspapers such as the Washington Bee, Cleveland Gazette, and New York Globe, quoted the Afro-American extensively. It is believed that the newspaper lasted into the 1890s. [3]

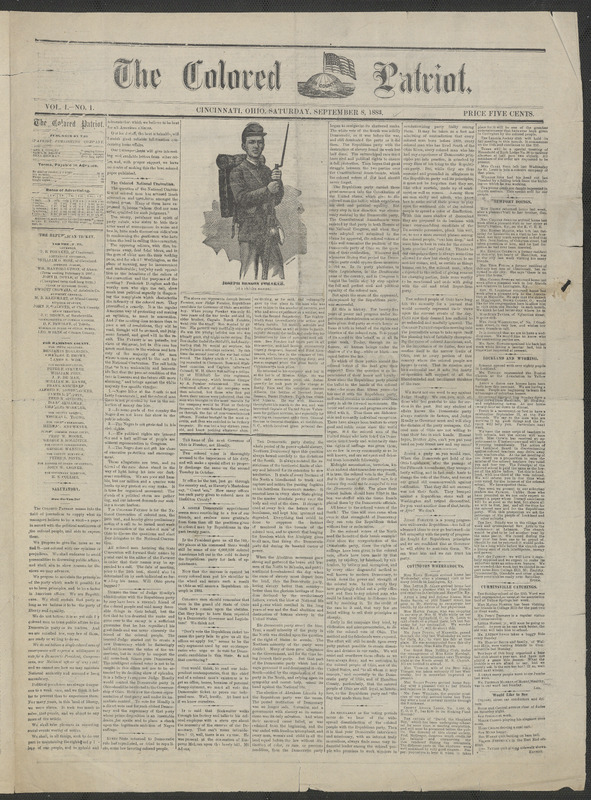

Colored Patriot (1883-?)

The Colored Patriot began in 1883 to be a Cincinnati-based weekly by the Patriot Publishing Company. Whereas the Afro-American was an organ of Black democrats, the newspaper voiced out Black Republicans. On its issue on December 8, 1883, it claimed, “The Patriot is the only Colored Republican paper published or printed in Cincinnati.” Its motto was “A paper in accord with the political sentiment of the Colored people.” A group of editors and agents worked for the newspaper: George E. Comely as managing editor, Samuel M. Brown as business manager, and Benjamin Hickman as traveling agent. The newspaper also had a local news team including Frank B. Kinney as city editor, J.M. Lewis, Charles Henson, and H.M. Griffin as social intelligence, T.P. Morgan as church intelligence, and John Tait and G.W. Stevens as secret order intelligence. In accordance with Black civil rights movement, the editors attended the national and state conventions of Black citizens, and reported on the 1883 National Convention on its first issue. Its ending date is unclear.

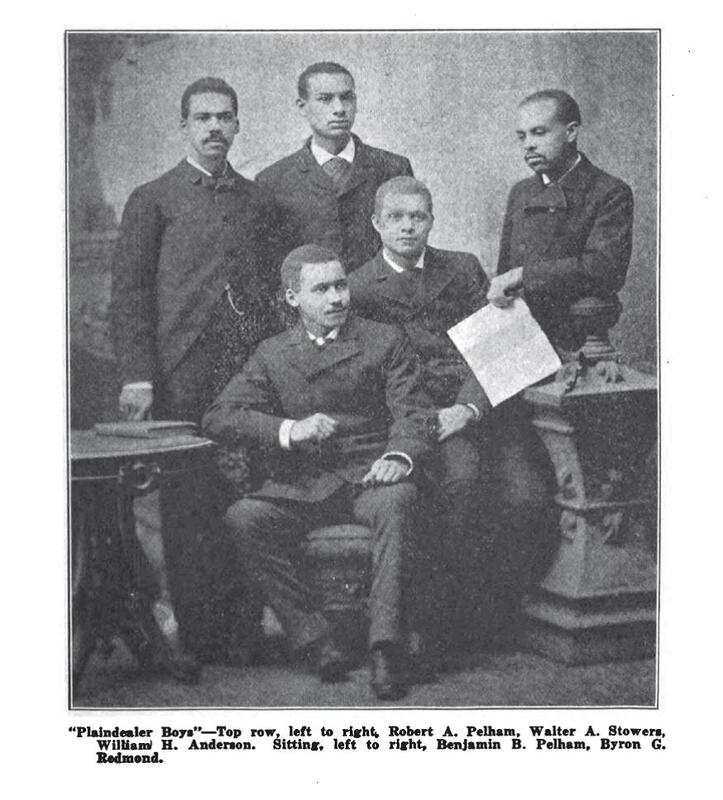

Plaindealer (1883-1893?)

The Plaindealer was a weekly newspaper, published by "The Plaindealer Company" in Detroit, Michigan and Cincinnati, Ohio simultaneously at its beginning for a while. However, how the newspaper was published in the two different urban areas, and how long this practice continued remains unclear. If it appeared in Cincinnati, Samuel B. Hill might have served as an editor from April 7 to May 19 1893. But, further record and information are needed to confirm the newspaper's relation to Ohio. Generally, it has been known that the newspaper was founded in 1883 by the brothers Benjamin and Robert Pelham Jr., along with Walter H. Stowers and W.H. Anderson. [4] The ending date is unclear.

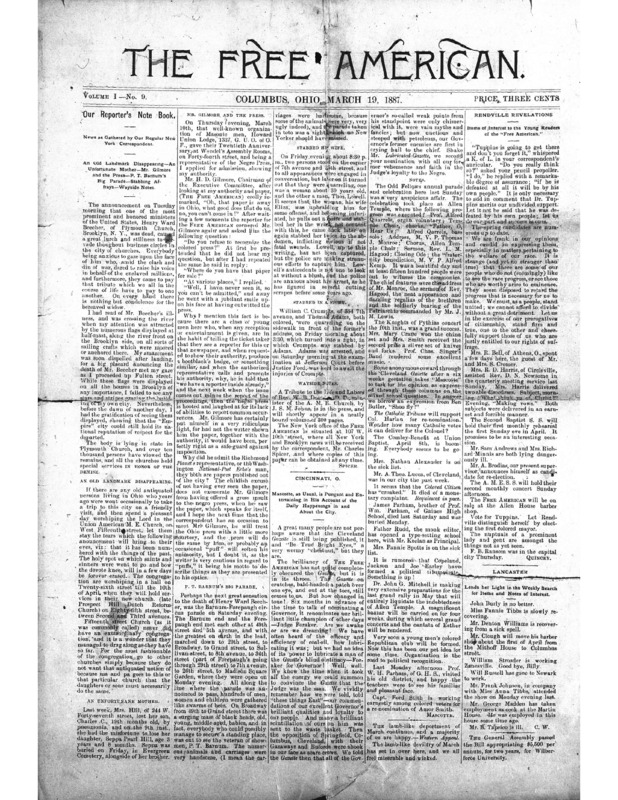

Free American (1887-1888)

Columbus Free American was published by Theodore A. Thompson and Walter S. Thomas. The paper presumably started in early 1887, but both dates of the first and last issues are unknown. Only one issue on March 19, 1887 survived. Any biographical information about the editors is also barely available. The newspaper had many correspondents who delivered local news including accidents, deaths, gatherings, and even gossip. The correspondents appeared not only in-state cities but also metropolitan areas such as New York City, where the newspaper agents also recruited subscribers. It seems that the Free American was in competition with the Cleveland Gazette, as one of the articles mocks the Gazette: “The brilliancy of THE FREE AMERICAN has not quite completely obscured the Gazette, but it is in its throes.”

You can learn more about Harry C. Smith's Cleveland Gazette and Paul Laurence Dunbar's Dayton Tattler in the following pages.

[1] Nell Painter, "Black Journalism, the First Hundred Years," Harvard Journal of Afro-American Affairs, 2 (1971): 39.

[2] Penn, The Afro-American Press and Its Editors, 1891. Reprinted by Arno Press (1969), 114.

[3] See Lawrence Grossman’s “In His Veins Coursed No Bootlicking Blood: The Career of Peter H. Clark,” Ohio History Journal (Spring 1977): 79-95.

[4] Penn, 159-160.