Rhyzomatic Democracy:

Visualizing Data of the Ohio Black Press in the 19th Century

The Ohio Black Press in the 19th century, centering African American and Black diasporic experience, uses data from the surviving newspaper issues to understand the communal life of early Black residents in Ohio. Three categories--topics (“what the subscribers read”), quoted periodicals (“what the editors reprinted”), and advertisements (“what the advertisers sold”)--were considered, as they appear consistently throughout all the papers in this project. The Palladium of Liberty exceptionally offers more data sources, as the newspaper lists its subscribers and agents, which allow us to observe the geographical network of Black communities such as national and state Colored Conventions beyond its base city, Columbus.

It is important to remember that the datasets should not function as final and representative figures of the Black newspapers in the period. Despite the project’s attempt to use datasets as accurately as possible, the incomplete data result from the short lifespans and scant issues of most Black newspapers in the 19th century due to insufficient resources to maintain publication. There are also inevitable errors and biases because of the arbitrary nature of creating data, needless to mention their incomprehensive coverage. For example, if an article reports that Black Ohioans petitioned state legislators to reform public education for Black children, it can be considered both “education” and “politics,” as they often overlap each other in case of African American experience. Similarly, are religious poems about “religion” or “literature”? Are articles about Civil War soldiers’ reunions about “politics,” “local news,” or “community events”? Those topics situated in-between multiple subsets were determined based on articles’ contents, tones, and emphases. The importance of a topic through its frequency and length is also measured in a relative term rather than with quantifiable exactitude because the size and length of columns varies in different newspapers.

Our concern about using data to quantify the life of early Black Ohioans is not limited to the arbitrariness and simplicity of categorization that reduces their humanity to mere numbers. We have a long history of peripherizing non-white-authored documents in preservation. Black and other ethnic newspapers have been less attentively archived than white publications at established institutions because of "the racially discriminatory nature of the archives and databases," according to Benjamin Fagan.[1] Even if there is any preserved document, its metadata is still problematic because it limits our scope on Black print culture, as Molly O’Hagan Hardy argues on the Printer’s File at the American Antiquarian Society.[2] This inequity resided in the publication, collection, and preservation of the Black press has gotten worse in our digital age. Available digital sources have been selected according to those who have access to resources and tools for digitization, which as a result further marginalizes groups of people who don’t have the same kind of access. For these reasons, this project recognizes that data visualization does not guarantee neutrality and objectivity but reflects how its creator interprets the historical documents by selecting, sampling, curating, and setting data to make the extant copies visible before they become too scattered to trace.

If the data is fated to be incomplete and they tell only fractions of the life of early Black Ohioans, what do we do with the datasets in this project? Data always tells more than quantified summaries of a text. The datasets here evince the project’s “effort to bring forth the full humanity of marginalized peoples through the use of digital platforms and tools,” which Kim Gallon calls the “technology of recovery.”[3] They convey the complicated backstory of a historical document authored by Black Americans, exposing the tension between the racist practice to delete the Black record and the force to (re)produce that record inside and outside of the racialized institution. By tracing the Black newspapers through historical documents and contemporary periodicals, securing their digitized images by contacting and visiting libraries and historical societies, and curating them in a way as readable, accessible, and sustainable as possible, this project joins the realm of Black DH studies that highlights the significance of Black presence in digital archives. The visualized data in the Ohio Black Press intends to decenter the “grand” narrative of America by making (hi)stories of African Americans available for the learning public. While aware of a representational simplicity of data that critical thinking in the humanities opposes, this project on the Black press offers both data and interpretative narratives about what data demonstrates and fails to reveal.

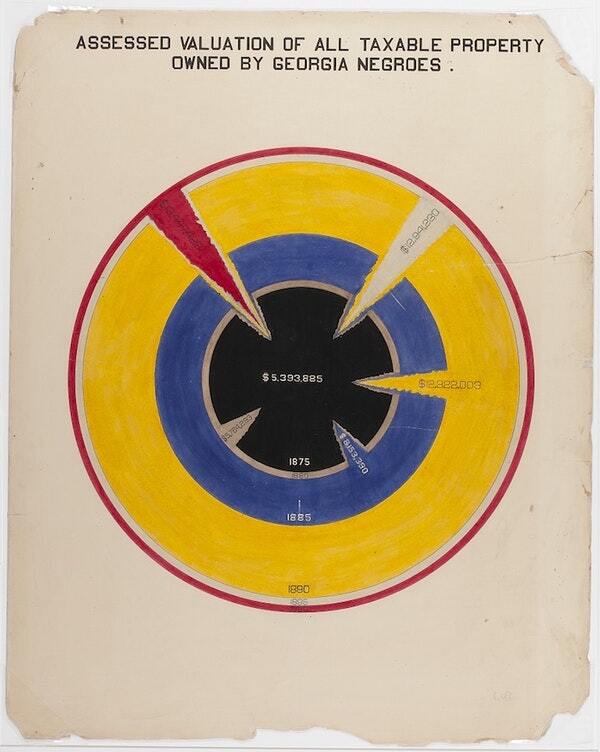

Using data to highlight African American experience from their perspective is not unprecedented. Black journalists used data to “assert their humanity, histories, knowledges, and expertise” against “the ways that technologies have historically been and continue to be used to disempower,” as Kelly Baker Joseph and Roopika Risam define the significance of data for Black Studies.[4] Let’s take examples from the newspapers here. In the inaugural issue of the Aliened American, William Howard Day questions the credibility of the data offered by the American Colonization Society that haphazardly calculated the total number of immigrants to Liberia only for its colonist agenda. Similarly, the Colored Citizen cites an article in the Richmond Examiner that implies the alleged incompetence of Black soldiers due to their susceptibility to diseases. Then, the paper refutes the article’s misleading statistics and rather uses the same number to reveal the mistreatment of wounded Black soldiers, who consequently died of secondary infections. Likewise, this project uses data to tell stories of Black Ohioans against an attempt to reinforce a single narrative about them.

The datasets on the Black newspapers in 19th-century Ohio are designed to enrich on-going studies of early African American literature and Black print culture, with a focus on Black citizenship. Many writings in 19th-century Black newspapers were published through anonymous, pseudonymous, and collaborative authorship, which P. Gabrielle Foreman identifies a “practice of simultaneous address” as one of the most distinctive aspects of African American literary tradition.[5] As Derrick Spires’ The Practice of Citizenship demonstrates, theoretical interventions into the study of Black print culture like periodicals can reveal African Americans’ complex negotiation with the reading public to achieve citizenship and maintain agency as democratic citizens. For example, these interactive maps [link] of ceaseless moves that agents of the Palladium of Liberty made beyond the geopolitical boundaries can demonstrate how actively African Americans practiced civic life, which especially evolved from state and national Colored Conventions.

Through the Ohio Black press in the 19th-century, this project emphasizes that African Americans have constantly created momenta to keep ideals of democracy evolving in everyday practice, which I call “rhizomatic democracy.” The visual image of “roots” stands for the interconnected, non-hierarchical, multiple, and distributed nature of the botanical rhizome, which resembles early Black Ohioans’ collective movements for full civil rights. The datasets of the Black newspapers in 19th-century Ohio exemplify how archives can encode and produce stories about Black community building, networks, and civic engagements that we still observe in our contemporary society.

For more datasets for the Ohio Black press in the nineteenth century, see this page. For the scripts used for some of the visualizations in this project, visit the Ohio Black Press Github page.

The visualizations and interactive maps on this site and Github page are developed by Dr. Jason Heppler, Senior web developer, at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media, George Mason University.

[1] Benjamin Fagan, "Chronicling White America," American Periodicals, vol. 26, no. 1 (2016): 12.

[2] Molly O’Hagan Hardy, “‘Black Printers’ on White Cards: Information Architecture in the Data Structures of the Early American Book Trades,” Debates in the Digital Humanities in 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

[3] Kim Gallon, “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities,” Debates in the Digital Humanities in 2016, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

[4] Kelly Baker Josephs and Roopika Risam, ed. The Digital Black Atlantic (University of Minnesota Press, 2021).

[5] P. Gabrielle Foreman, Activist Sentiments: Reading Black Women in the Nineteenth Century (University of Illinois Press, 2009), 4.